|

|

|

|

Femoral hypoplasia-unusual facies syndrome (FHUFS) is a rare and sporadic condition comprised of multiple congenital malformations including bilateral femoral hypoplasia and characteristic facial features [1,2]. Patients with FHUFS may undergo various operations whether those procedures are associated with the syndrome or not. This syndrome is known to cause anesthesia-related problems during surgery such as difficulty in endotracheal intubation and others resulting from multiorgan involvement. We want to share our experience of a patient with FHUFS, and discuss some anesthetic considerations during the perioperative period.

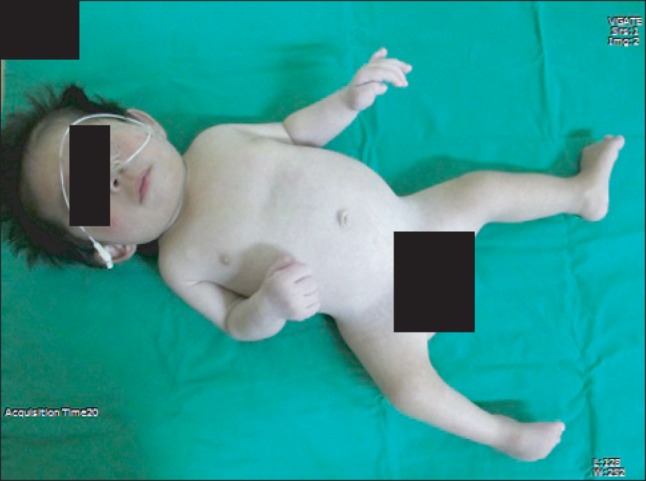

A 33-month-old girl (height 60 cm, weight 6.5 kg) presented for repair of cleft palate and correction of club foot. Her mother was suffering from diabetes mellitus for 5 years and her two siblings were healthy. The patient was delivered by Cesarean section at 35 weeks of gestation. At birth, she had multiple anomalies including femoral hypoplasia, club foot, syndactyly of the second and third toes, spina bifida with a deformity in the sacroiliac joint, cleft palate and a small mandible, but showed no abnormalities in the cardiac and renal systems. She was diagnosed with femoral hypoplasia-unusual facies syndrome (Fig. 1). The patient was physically retarded for her age, but preoperative routine laboratory values were within normal limits.

She arrived at the operating room without premedication, and was monitored with an electrocardiogram, a non-invasive blood pressure monitor and a pulse oximeter. Her baseline heart rate was 125 beats/min, and oxygen saturation was 95% in room air.

Anticipating problems with endotracheal intubation, we prepared various laryngoscope blades, stylets, soft tip introducer, and laryngeal mask airways. However, pediatric fiberoptic bronchoscope was not available. Anesthesia was induced by inhalation of 7-8% sevoflurane in 100% oxygen via a face mask. After confirmation of adequate ventilation and placement of an intravenous catheter, 5 mg of rocuronium and 0.1 mg of atropine were administered. The patient was placed supine with the shoulders slightly elevated above the level of a rolled towel. At first, tracheal intubation was attempted using a laryngoscope with a Miller No. 1 blade, but the straight blade was too narrow to push her large tongue aside. Thus, we decided to use a Macintosh No. 1 blade, but it did not fit her tongue, either. The glottic view was Cormak and Lehane grade IV (no epiglottis visible). We added some pads underneath her shoulders to make them elevate a little higher, and another experienced anesthesiologist tried intubation again with a Macintosh No. 2 blade. The lowest part of the glottis opening was visible with external pressure on the cricoid cartilage. A cuffed endotracheal tube (internal diameter 3.5 mm) was placed carefully with a stylet. One mg of dexamethasone was administered to prevent soft tissue edema.

Surgery took 8 hours and was uneventfully. The patient's vital sign was stable during operation. Fearing airway edema, the baby was transferred to intensive care unit with intubated state. She was extubated 2 days after surgery without complications.

FHUFS, also known as femoral-facial syndrome, was described by Daentl et al. in 1976 [1]. The definitive etiology is not known although its relationship with maternal diabetes has been suggested [2]. As its designation indicates, FHUFS is characterized by bilateral femoral hypoplasia and distinguishing facial features including upslanting eyes, short nose with a broad tip, long philtrum, thin upper lip, micrognathia and cleft palate. Other skeletal malformations such as vertebral defect, club foot or upper extremity deformities are also observed. FHUFS can also be accompanied by lung hypoplasia, cardiac defect, or anomalies in the central nervous or genitourinary system [1,2]. Cardiac problems are more common in patients with sacral agenesis or mixed cases with femoral and spinal involvement compared to those with normal spine [2]. Therefore, preoperative systemic evaluation is needed in patients with FHUFS for safe anesthetic management.

Our patient had a cleft palate and a small lower jaw, and thus, difficult laryngoscopy was expected. According to Gunawardana's study of pediatric patients undergoing repair of cleft lip and palate, the incidence of difficult laryngoscopy (Cormack and Lehane grade III and IV) was 45.76% in patients with bilateral cleft lips and 34.61% in those with retrognathia [3]. Mandibular hypoplasia also makes intubation using a laryngoscope difficult as it compels the tongue to the relatively posterior portion within the oropharynx and disturbs visualization of the vocal cords [4]. Patients with FHUFS may have a cleft palate and/or a small mandible, and thus contributing to the higher incidence of difficult airway. Iohom et al. [5] reported successful fiberoptic intubation through a laryngeal mask airway while maintaining spontaneous respiration in a 3-month-old infant with this syndrome, in whom direct laryngoscopy was impossible.

In infants and small children, straight-blade laryngoscopes are preferred and easier to use for intubation. In certain populations of patients whose tongues are relatively large, however, a curved blade is likely to be more useful as it retracts the tongue more easily. Laryngoscopy using a curved blade may be helpful in infants with Beckwith-Weideman syndrome, trisomy 21 or Pierre-Robin syndrome [4]. At first, we tried to intubate our patient with a straight-blade laryngoscope but replaced it with a curved-blade one because of her large tongue.

It is recommended that intubation attempts using a direct laryngoscope not be allowed more than three times as the pediatric airway is very susceptible to trauma. When managing the pediatric difficult airway, experienced anesthesiologists should be available for help with securing the airway. Sometimes, gentle pressure on the larynx, which makes the glottis more visible, is necessary for successful laryngoscopy [4].

Besides difficulties in endotracheal intubation, anesthetic considerations for patients with FHUFS include close attention during neuraxial anesthesia, positioning, and intravenous access due to accompanied anomalies of the vertebra, rib, upper extremities or femur [5]. Defects in the cardiopulmonary or central nervous system and the genitourinary tract can also influence anesthetic management.

In conclusion, patients with FHUFS may have various abnormalities that can cause difficult laryngoscopy and necessitate special anesthetic strategies. Careful preoperative assessment of the affected systems, detailed planning, proper preparation, and teamwork are required for successful anesthetic management.

References

1. Daentl DL, Smith DW, Scott CI, Hall BD, Gooding CA. Femoral hypoplasia-unusual facies syndrome. J Pediatr 1975; 86: 107-111. PMID: 1110431.

2. Burn J, Winter RM, Baraitser M, Hall CM, Fixsen J. The femoral hypoplasia-unusual facies syndrome. J Med Genet 1984; 21: 331-340. PMID: 6502648.

3. Gunawardana RH. Difficult laryngoscopy in cleft lip and palate surgery. Br J Anaesth 1996; 76: 757-759. PMID: 8679344.

4. Infosino A. Pediatric upper airway and congenital anomalies. Anesthesiol Clin North America 2002; 20: 747-766. PMID: 12512261.

5. Iohom G, Lyons B, Casey W. Airway management in a baby with femoral hypoplasia-unusual facies syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth 2002; 12: 461-464. PMID: 12060336.

- TOOLS