|

|

|

|

Intubation of patients with major intraoral arterial bleeding is a challenge for anesthesiologists. We succeeded orotracheal intubation with a lightwand, but the orotracheal intubation tube was exchanged with a nasotracheal intubation tube for a surgical approach. We successfully changed the orotracheal to the nasotracheal intubation tube with a fiberoptic bronchoscope (FOB).

A 29-year-old man, 170 cm in height and 59 kg in weight, without any previous medical problems was admitted to the emergency room for the treatment of postoperative intraoral bleeding. Two days earlier, the patient underwent plastic surgery at a local clinic to revise his square jaw. During the operation, the right external carotid artery was lacerated. After the surgery, the surgeon applied gauze packing to the bleeding site for hemostasis and the wound was left open. The hemodynamic status of the patient was stable for one day at the local clinic. The surgeon had planned to close the wound site after hemostasis, however bleeding continued. When the patient arrived in the operating room, he was alert and without dyspnea. He could open his mouth fully despite postoperative pain. The patient's initial oxygen saturation was 100%. His heart rate was 123 beats/min, and his blood pressure was 108/63 mmHg.

Before anesthesia induction, pre-oxygenation through an oxygen mask at a rate of 5 L/min was performed. Glycopyrrolate 0.004 mg/kg was administered intravenously as a premedication. We maintained the patient in the reverse Trendelenburg position to prevent aspiration. We did not perform awake intubation because of patient's anxiety and pain. Anesthesia was induced with propofol 0.6 mg/kg and sevoflurane at a concentration of 2% in oxygen. A small dose of propofol was administered to prevent hypotension. Fortunately, mask ventilation was partially possible and SpO2 remained at 100%.

Upon laryngoscopic examination, no part of the glottis was visualized due to the presence of the packed gauze and intraoral hematoma. We were unable to identify the airway or normal anatomy of the pharynx. We attempted fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation. The FOB was passed through the pharynx, but the vocal cords were not visualized due to the hematoma and gauze in the oropharynx. Intubation with the FOB failed. Next, we considered administering a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), but LMA was not guaranteed to prevent aspiration. The lightwand was chosen to maintain ventilation and it provided a more secure airway than LMA [1]. We successfully intubated the patient in the second attempt with a lightwand.

The surgeon requested nasal intubation for surgical approach. A nasal intubation tube was advanced through the naris and FOB was advanced through the nasotracheal tube and inserted close to the anterior commissure of the vocal cord along with the orotracheal tube. Under examination with the FOB, we checked the balloon of the orotracheal tube and deflated the balloon. Then, the FOB was advanced to the carina. After the orotracheal tube was carefully removed, the nasotracheal intubation tube was railroaded slowly over the FOB. After intubation, the tracheal tube position was verified by auscultating equal bilateral breath sounds as well as by monitoring EtCO2.

The surgery involved controlling the patient's bleeding using an extra oral approach with electrocoagulation of the right external carotid artery and the use of topical hemostatic agents. When the surgery was finished, extubation was not performed due to intraoral edema and the possibility of rebleeding. The patient was sent to the intensive care unit (ICU). Two days later, he was extubated and discharged from the ICU without any complications.

Although orotracheal intubation was successful in this difficult airway, we had to change the orotracheal tube to a nasotracheal tube for surgery. A new lightwand (TrachlightŌäó) with a brighter light source and flexible stylet permitted oral and nasal intubation under ambient light. In a reported case, the soft lightwand was inserted easily and with a mild hemodynamic response into a double-curve nasotracheal tube [2]. However, we had not a soft, flexible lightwand, so we could not perform the nasal approach. We just performed orotracheal intubation with a lightwand, and decided to exchange the oral endotracheal tube with a nasal endotracheal tube using an FOB.

There have been several methods described for the conversion of oral to nasal endotracheal tubes. One case report a cook airway exchange catheter being used successfully in a patient with mandibular atrophy [3]. However, the exchange catheter has the possibility of inadvertent dislodgement and can be dangerous in patients with a difficult airway.

As a method that was reported previously, orotracheal tube to nasotracheal tube change with a FOB like a retrograde intubation method was reported [4]. The limitations of this method are the possibility of the optical fibers breaking, trauma, failure, and inadvertent extubation.

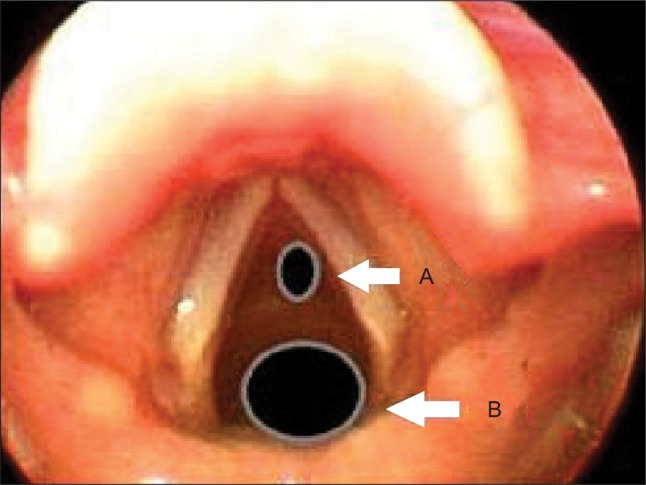

The technique we used in our case is easy because it advances along with orotracheal intubation tube. It is also safe because we continuously monitored the tip of the FOB located in carina. Nevertheless, careful manipulation is required to go through the anterior commissure of vocal cord, because it has small room to pass due to preexisting orotracheal intubation tube (Fig. 1).

In conclusion, FOB is a reliable and safe method for changing to nasotracheal intubation tube in patients with preexisting orotracheal intubation tube.

References

1. Henderson JJ, Popat MT, Latto IP, Pearce AC. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for managementof the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia 2004; 59: 675-694. PMID: 15200543.

2. Cheng KI, Chang MC, Lai TW, Shen YC, Lu DV, Lai ST, et al. A modified lightwand-guided nasotracheal intubation technique for oromaxillofacial surgical patients. J Clin Anesth 2009; 21: 258-263. PMID: 19502038.

3. Salibian H, Jain S, Gabriel D, Azocar RJ. Conversion of an oral to nasal orotracheal intubation using an endotracheal tube exchanger. Anesth Analg 2002; 95: 1822PMID: 12456473.

4. Dutta A, Chari P, Mohan RA, Manhas Y. Oral to nasal endotracheal tube exchange in a difficult airway: a novel method. Anesthesiology 2002; 97: 1324-1325. PMID: 12411827.

Fig.┬Ā1

We advanced the fiberoptic bronchoscope (FOB), which was passed via the naris along the occupied orotracheal tube and inserted close to the anterior commissure of the vocal cords, to the carina. After the FOB reached the carina, the occupied orotracheal tube was carefully removed and the nasotracheal intubation tube was railroaded slowly over the FOB. A: Fiberoptic bronchoscope, B: Orotracheal intubation tube.

- TOOLS