Effects of a fentanyl-propofol mixture on propofol injection pain: a randomized clinical trial

Article information

Abstract

Background

Propofol injection pain is a common problem that can be very distressing for patients. We compared the effects of injection with saline followed by injection with a fentanyl-propofol mixture, injection with fentanyl followed by a propofol injection, and injection with saline followed by propofol alone on propofol injection pain.

Methods

The patients were assigned randomly to one of three groups. A rubber tourniquet was placed on the forearm to produce venous occlusion for 1 min. Before anesthesia induction, group C (control, n = 50) and group M (fentanylpropofol mixture, n = 50) received 5 ml of isotonic saline, while group F (fentanyl, n = 50) received 2 µg/kg of fentanyl. After the tourniquet was released, groups C and F received 5 ml of propofol and group M received 5 ml of a mixture containing 20 ml of propofol and 4 ml of fentanyl. At 10 s after the study drugs were given, a standard question about the comfort of the injection was asked of the patient. We used a verbal rating scale to evaluate propofol injection pain. Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t-tests and Fisher's exact tests; P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The demographic data were similar among the groups. In group M, the number of patients reporting propofol injection pain was significantly lower than in groups F and C (both P < 0.001). No patient in group F or M experienced severe pain, whereas 24 patients (48%) had severe pain in group C (both P < 0.001).

Conclusions

This study shows that a fentanyl-propofol mixture was more effective than fentanyl pretreatment or a placebo in preventing propofol injection pain.

Introduction

Propofol has gained wide acceptance among anesthesiologists due to its favorable induction characteristics, including its rapid onset time and fast elimination half-life. However, intravenous (i.v.) propofol injections are painful, making the induction of anesthesia uncomfortable for the patient and anesthesiologist [1234].

Several pharmacological interventions have been described to reduce or prevent propofol injection pain [3], including cooling or diluting the propofol solution, or applying propofol in tandem with local anesthetics, ondansetron, ketamine, magnesium sulfate, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or opioids [56789101112].

Fentanyl given just before propofol diminishes propofol injection pain, but it is unclear whether fentanyl has this effect when used in a mixture with propofol [4]. We compared the effects of injection with saline followed by injection with a fentanyl-propofol mixture, injection with fentanyl followed by a propofol injection, and injection with saline followed by propofol alone on propofol injection pain. We hypothesized that a fentanyl-propofol mixture might reduce the pain related to propofol injection more effectively than fentanyl pretreatment alone.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted with Institutional Review Board approval and was registered with the www.clinicaltrials.gov protocol registration system (NCT02203175). Ethical approval (No. 100: 25/05/2011) was provided by the Ethics Committee of Yeditepe University Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey (Chairperson: Dr. Kemal Saricali), on May 25, 2011. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Study data were collected at Yeditepe University Hospital from April 2011 to April 2012. In total, 150 American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I-II patients, aged 18-65 years old, who were scheduled for elective surgery were enrolled. The exclusion criteria were communication difficulties, psychiatric and neurological disorders, history of allergy to the study drugs, and use of analgesics or sedative drugs within 24 h before surgery.

The study was designed in a prospective, randomized, and double-blind fashion. Patients were assigned randomly to one of three groups using an Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA)-generated randomization table. No patient received premedication. Before the induction of anesthesia, it was explained to the patients that they would be receiving i.v. anesthetics that might cause pain in the forearm. On arrival at the operating room after monitoring (ECG, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximeter, and bispectral index [BIS]), a 20-gauge cannula was inserted into a vein on the dorsum of the patient's non-dominant hand and a 0.9% NaCl infusion was started at 5 ml/kg/h for 5 min.

Next, the i.v. infusion was stopped and the arm with the i.v. line was elevated for 15 s to facilitate gravity drainage of venous blood. A rubber tourniquet was placed on the forearm to produce venous occlusion for 1 min. The anesthesiologist who pretreated the patients was blinded to each patient's allocation. Before anesthesia induction, the subjects in groups C (control, n = 50) and M (mixture, n = 50) received 5 ml of isotonic saline, whereas those in group F (fentanyl, n = 50) received 2 µg/kg of fentanyl diluted with saline to a total volume of 5 ml as a pretreatment (1% propofol [Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany]; 0.05 mg/ml fentanyl [Janssen-Cilag Pty. Ltd., Macquarie Park, Australia]) at an injection rate of 0.5 ml/s.

The drugs were prepared by one of the investigators, who was blinded to the study groups. The pretreatment solutions were identical in appearance. All study drugs were prepared preoperatively at room temperature. The pH values of the fentanyl, propofol, and fentanyl-propofol solutions were measured with a pH meter (InoLab 740 with terminal 740; WTW GmbH, Weilheim in Oberbayern, Germany). For the patients in group M, the mixture of fentanyl and propofol was prepared using 20 ml of propofol and 4 ml of fentanyl. After the tourniquet was released, the patients in groups C and F received 5 ml of propofol whereas the patients in group M received 5 ml of the fentanyl-propofol mixture at an injection speed of 0.5 ml/s.

At 10 s after the study drugs had been given, a standard question about the comfort of the injection was asked of the patient. We used a verbal rating scale (VRS) to evaluate the severity of pain due to the injection of propofol [5101112]: 0, none (negative response to questioning); 1, mild pain (pain reported only in response to questioning without any behavioral signs); 2, moderate pain (pain reported in response to questioning and accompanied by behavioral signs or pain reported spontaneously without questioning); or 3, severe pain (strong vocal response or response accompanied by facial grimacing, arm withdrawal, or tears). All patients were able to answer the question; additionally, in all patients the BIS was above 80 at the time of questioning.

The remaining dose of propofol and fentanyl was then given to complete the induction of anesthesia. The complete induction dose was 2 mg/kg of propofol and 2 µg/kg of fentanyl. All patients were given 0.5 mg/kg of atracurium for muscle relaxation. Because groups F and M had already received 2 µg/kg of fentanyl, only the patients in group C received 2 µg/kg of fentanyl after the muscle relaxant. After orotracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with 1.0-2.0% sevoflurane and 60% nitrous oxide in oxygen with controlled mechanical ventilation.

The primary outcome was a complete response (no injection pain, VRS = 0). The secondary outcome was propofol injection pain.

Statistical analysis

Propofol injection pain was the primary outcome. The reported incidence of propofol injection pain is ~70%; to decrease this incidence to 35%, it was calculated that 49 patients would be needed in each group with a type I error of 0.05 and power of 90%. Due to possible subject drop-out, 50 patients per group were entered into the study.

Demographic data were compared using Student's t-test. Fisher's exact test and χ2 tests were used to assess differences between categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

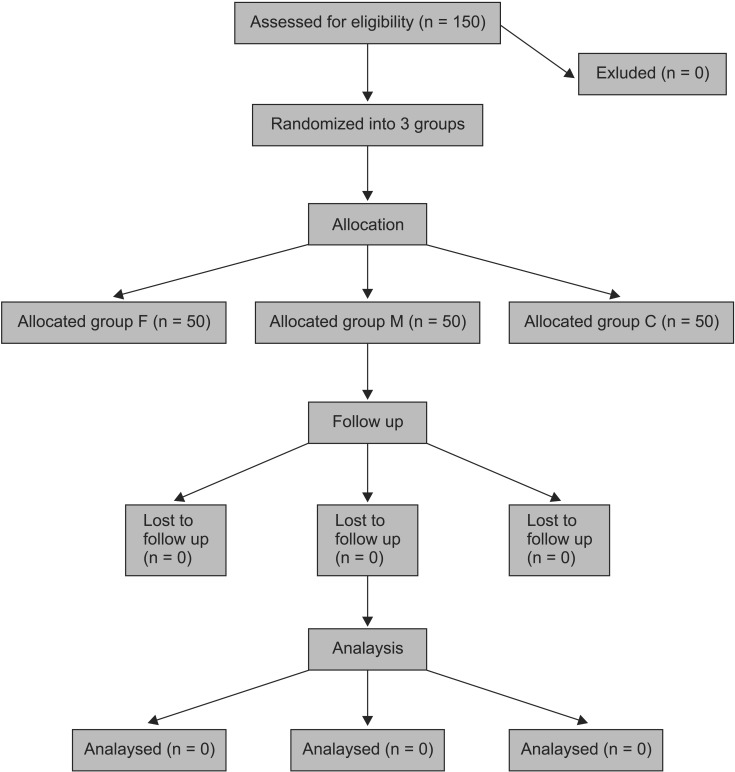

In total, 150 patients were studied. Fig. 1 shows a flow chart of the study, and Table 1 shows the demographic data for the patients. There was no significant difference in age, weight, or sex among the three groups. The incidence and severity of propofol injection pain are shown in Table 2.

In all cases, it was possible to obtain clear answers from the patient before the patient became anesthetized. The overall incidence of propofol injection pain was 100% (50/50) in group C, 92% (46/50) in group F, and 64% (32/50) in group M. The overall incidence of propofol injection pain in group F was not different from that in group C, whereas the incidence in group M was significantly lower than that in group C (P = 0.0001). Compared with group F, the incidence of propofol pain in group M was significantly lower (P = 0.001).

In group C, 48% of the patients (24/50) experienced severe pain, whereas no patient did in groups F and M (significance between group F and group M compared with group C, P = 0.0001 and 0.0001, respectively).

The incidence of patients with moderate pain was significantly lower in group M (16%; 8/50) than in group C (40%; 20/50; P = 0.013). There was no difference in the incidence of moderate pain between groups F and C.

In both groups F and M, the incidence of mild pain was significantly higher than in the control group (P = 0.009 and 0.0002, respectively). No difference was found between groups F and M with respect to mild pain.

The pH values of the propofol, fentanyl, and fentanyl-propofol solutions were 8.04, 4.45, and 7.42, respectively.

Discussion

Our results indicate that the mixture of fentanyl and propofol significantly reduced the incidence and severity of propofol injection pain compared with the control group. In contrast, fentanyl pretreatment did not reduce the incidence or severity of pain compared with the control group.

Although the mechanism underlying propofol injection pain is unclear, many factors affect the incidence of pain, including the site of injection, size of the vein, speed of injection, propofol concentration in the aqueous phase, buffering effect of the blood, speed of intravenous carrier fluid, temperature of the propofol solution, syringe material, and the concomitant use of drugs (e.g., local anesthetics and opioids) [12].

Several methods have been described to reduce propofol injection pain, including the use of a larger vein and pretreatment with pharmacological agents such as lidocaine, opioid analgesics, ketamine, meperidine, metoclopramide, diphenhydramine, magnesium sulfate, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents [456789101112131415]. The effects of temperature and dilution as well as varying the infusion rate have also been studied [16171819].

Propofol injection pain can be immediate or delayed. It has been suggested that immediate pain results from a direct irritant effect, whereas delayed pain may be caused by an indirect effect via the kinin cascade [20].

The site of action of opioids in reducing propofol injection pain may be central or peripheral [21]. Opioid receptors on peripheral terminal afferent nerves can mediate potent antinociceptive effects [22].

In this study, we used a tourniquet to isolate the arm veins from the rest of the circulation. This has been suggested to be a useful model for studying the peripheral actions of a drug [23].

The pH values of the propofol, fentanyl, and fentanylpropofol solutions were measured in our laboratory (8.04, 4.45, and 7.42, respectively). Because the pH value of fentanyl is lower than that of propofol, the pH value of the propofol-fentanyl mixture was lower than that of propofol alone. Eriksson et al. [24] reported that decreasing the pH of propofol resulted in a lower concentration of propofol in the aqueous phase.

Klement and Arndt [25] suggested that the concentration of propofol in the aqueous phase was a determining factor in propofol injection pain. In a bolus injection, only the outer aqueous phase comes into contact with the intima of the vein, and venous pain on administration of the irritating agent may be caused primarily by the concentration of the irritating agent in the aqueous phase [26]. Lowering the pH value of propofol by mixing it with fentanyl may explain the decreased incidence of propofol injection pain. Helmer et al. [26] reported a significant reduction in the incidence of propofol injection pain, from 40 to 16%, with the use of fentanyl before propofol. These incidences are much lower than the ones in our study. In our study, pain incidence was 100% in the control group and 92% in the fentanyl pretreatment group. These differences may be due to methodological differences between the two studies. In Helmer's study [26], patients were asked about pain after receiving 1.5 mg/kg of propofol and the BIS was not monitored. It is possible that after this dose of propofol, the patients were too deeply sedated to answer the question about pain correctly. This may explain why the reported incidence was so low compared with that in our study. Another reason may be the vein and i.v. cannula size (17 vs. 20 G) used in their study compared with ours, which may influence the incidence of propofol injection pain [27].

When mixing two drugs, major concerns are compatibility and the stability of the mixture. In our study, no precipitation was observed in the syringe. Stewart et al. [27] stated that propofol and fentanyl were compatible and stable when mixed together. The subjective nature of the four-point injection pain evaluation scale is a limitation of our study. Another limitation is that this method cannot be applied without tourniquet use.

In conclusion, fentanyl mixed with propofol reduced injection pain significantly compared with the control and fentanyl pretreatment groups.