Comparison of hemodynamic changes between old and very old patients undergoing cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty under spinal anesthesia

Article information

Abstract

Background

The old age population, including the very old aged (≥ 85 years), is rapidly increasing, and femur neck fracture from accidents is commonly seen in the elderly. Use of bone cement during bipolar hemiarthroplasty can cause bone cement implantation syndrome.

Methods

This study was prospectively conducted on the elderly who were scheduled to undergo elective cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty under spinal anesthesia. Patients were divided into 2 groups: the old age (65-84 years) and very old age groups (≥ 85 years). Hemodynamic parameters were recorded at the following time points: the start of the operation, femoral reaming, cement insertion, every 2 minutes after cement insertion for 10 minutes, femoral joint reduction, and the end of operation. When hypotension occurred, ephedrine was given.

Results

Sixty-five patients in the old age group and 32 patients in the very old age group were enrolled. Mean ages were 78.9 and 89.4 years, respectively, in the old age and very old age groups. The very old age group showed constantly decreased levels of cardiac index and stroke volume from cementing until the end of the operation compared to the old age group. To maintain hemodynamic stability after cement insertion, the requirement of ephedrine was higher in the very old age group than in the old age group (13.52 ± 7.76 vs 8.65 ± 6.38 mg, P = 0.001).

Conclusions

Bone cement implantation during bipolar hemiarthroplasty may cause more prominent hemodynamic changes in very elderly patients. Careful hemodynamic monitoring and management are warranted in very elderly patients undergoing cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty.

Introduction

The elderly population is rapidly increasing throughout the world due to improvement in healthcare. In 2010, 13.0% (40 millions) of the U.S. population were over 65 years old [1]. This phenomenon is also observed in Korea where the ≥ 65 age population grew from 7.3% (370,000) in 2000 to 11.2% (5,400,000) in 2010. The same is true in the very old age population (≥ 85 years). The ratio of the very old age population to the old age population (≥ 65 years) has increased from 5.13% (173,000) to 6.67% (370,000) during the same 10-year period [2]. Consequently, more geriatric patients are entering the operating room than ever before. These geriatric patients suffer from comorbid illness and decreased cardiopulmonary reserve, which pose physiological and technical challenges to anesthesiologists [3].

Femur neck fracture from accidents is commonly seen in the elderly mainly due to osteoporosis, coexisting disease, and an increased incidence of trivial trauma [4]. One of the effective treatments for femur neck fractures in the elderly is cemented bipolar hemiathroplasty. This operation enables patients to quickly regain the prefracture level of activity and to prevent bed sores [5]. However, use of bone cement during hemiarthroplasty can cause bone cement implantation syndrome (BCIS), which consists of hypotension, hypoxia, arrhythmia, and even cardiac arrest [6]. The severity of these symptoms is thought to be associated with patient risk factors, such as age, comorbid illness, cardiopulmonary reserve, and intertrochanteric femur fracture [7,8].

Hemodynamic monitoring to detect BCIS is essential during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. The measurement of cardiac output and stroke volume allows qualitative evaluation of pulmonary embolization during a pericementation period [7,9]. We assumed that hemodynamic changes during cemented hemiarthroplasty are susceptible to very elderly patients due to the aging process. Hence, we compared hemodynamic changes via the measurement of cardiac index and stroke volume between the elderly (65-84 years) and the very elderly patients (≥ 85 years) during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty.

Materials and Methods

With Institutional Review Board approval and patients' consent, this study was prospectively conducted on the old age patients over the age of 65 years who were scheduled to undergo elective cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty due to intertrochanteric fracture of the femur in 2011-2012. Spinal anesthesia was performed and bipolar hemiarthroplasty with bone cement was done by a single surgeon during the study period. After data collection, patients were divided into 2 groups according to age: the old age (65-84 years) and very old age groups (≥ 85 years). Patients who refused spinal anesthesia or were ineligible for regional anesthesia due to dementia, coagulation abnormalities, history of spine surgery, and poor reserve of cardiopulmonary function were excluded from the study. Prior to induction of anesthesia, coexisting disease was examined and consulted to a specialist as needed for the evaluation of risk associated with anesthesia and operation. Echocardiography for the evaluation of cardiac function and lumbar spine X-ray for the assessment of deformities were performed on all patients.

All patients received spinal anesthesia using 10 µg of fentanyl in addition to 9-10 mg of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine administrated at the lumbar level (L3-4 or L2-3) to achieve a sensory level of T10 in the lateral position, with the fracture site faced down. After performing spinal block, patients were maintained in the lateral position for 15 minutes to minimize hemodynamic changes, 5 ml/kg of normal saline was administered during spinal anesthesia to prevent hypotension during the operation, and 2 L/min of oxygen was continuously given through the nasal cannula. Electrocardiogram, heart rate, and oxygen saturation were monitored continuously during the operation, and a 20-gauge catheter was inserted into the radial artery for direct arterial pressure monitoring. The radial arterial catheter was connected to FloTrac sensors™ (Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Irvine, CA, USA) to measure cardiac output, stroke volume, and cardiac index by using the algorithm provided in the commercially available Vigileo™ APCO system (Edwards Lifesciences LLC; software version 3.0). After the sensory level was checked and hemodynamic stability was confirmed, patients were placed in the lateral decubitus position for surgery. Cardiac index, stroke volume, mean blood pressure, and heart rate as hemodynamic variables were recorded at the following time points: the start of the operation, femoral canal reaming, immediately after cement insertion, every 2 minutes after cement insertion for 10 minutes, femoral joint reduction, and the end of the operation.

Hypotension was defined as > 20% reduction in systolic blood pressure compared to systolic pressure at the start of the operation as baseline or a systolic pressure of < 90 mmHg. Blood pressure was supported with intravenous ephedrine in 4 mg increments, and ephedrine was repeatedly injected if hypotension was persistent. When hypotension, bradycardia, and oxygen desaturation occurred as signs of bone cement implantation syndrome during a pericementation period, epinephrine injection and high-flow oxygenation through a mask were performed as life support. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was immediately performed if obtundation of mental status, severe hypotension, and hypoxia were sustained. Packed red blood cells were given to reach or maintain 10 g/dl of hemoglobin during the operation.

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 18.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) to analyze data and G* power version 3.17 (Franz Faul, Universitat Kiel, Germany) to determine sample size. All data are expressed as the number of patients or mean ± SD or mean ± SE. Student 2-tailed t test was used to compare the used amount of packed red blood cells, the requirement dosage of ephedrine, and other quantitative variables of demographic data between the 2 groups. Categorical variables, such as coexisting disease, were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Repeated measured ANOVA was used to compare cardiac index, stroke volume, mean blood pressure, and heart rate as hemodynamic variables during the observation period between the 2 groups. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Paired t test was used to detect hemodynamic data changes compared to the start level of operation. For the purpose of correcting for multiple testing, statistical significance was specified by means of the Bonferroni correction. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A sample size of > 72 for the repeated measured ANOVA was needed to have an 80% power (β = 0.20) of detection the effect size F 0.25 (α = 0.05).

Results

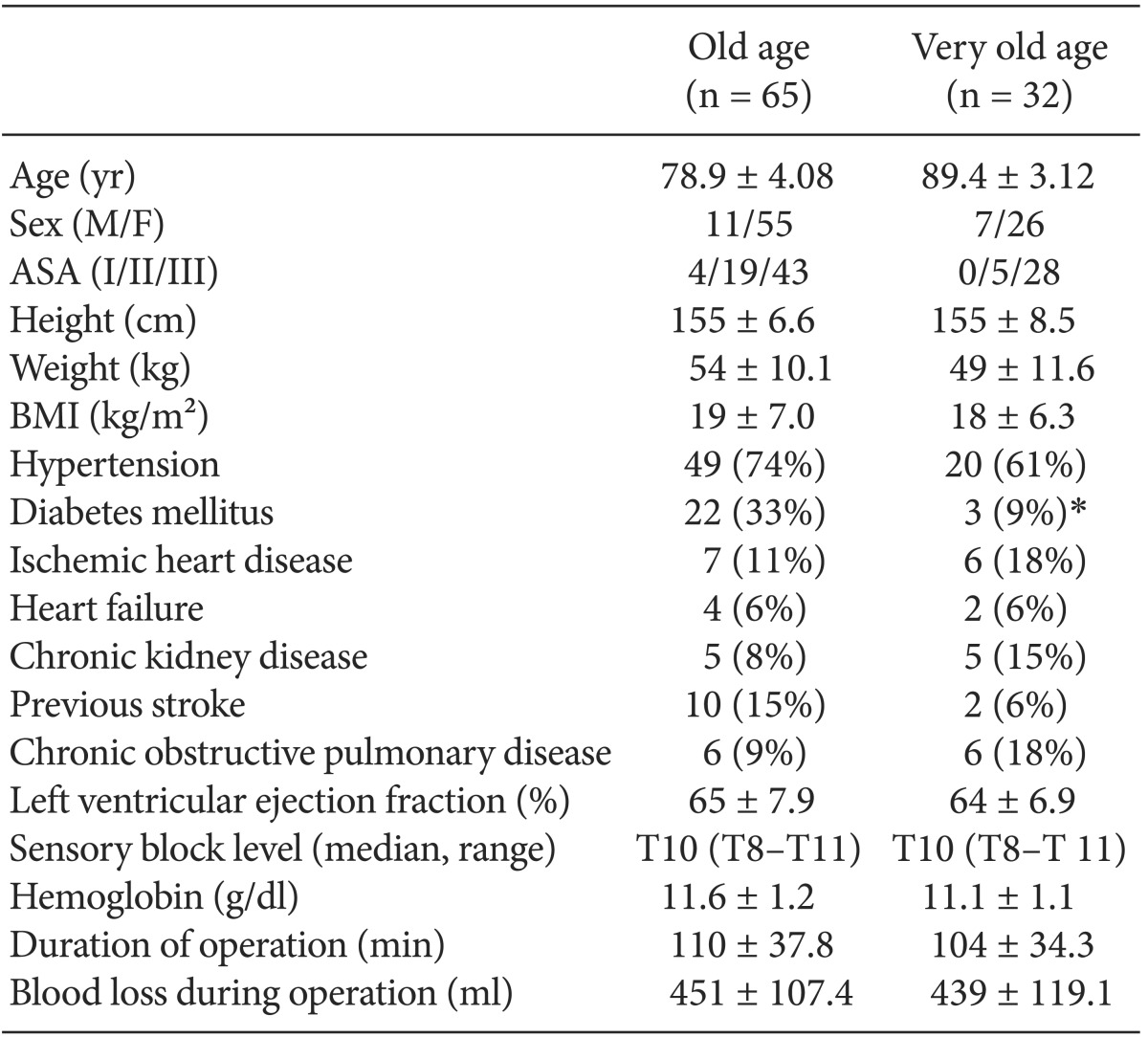

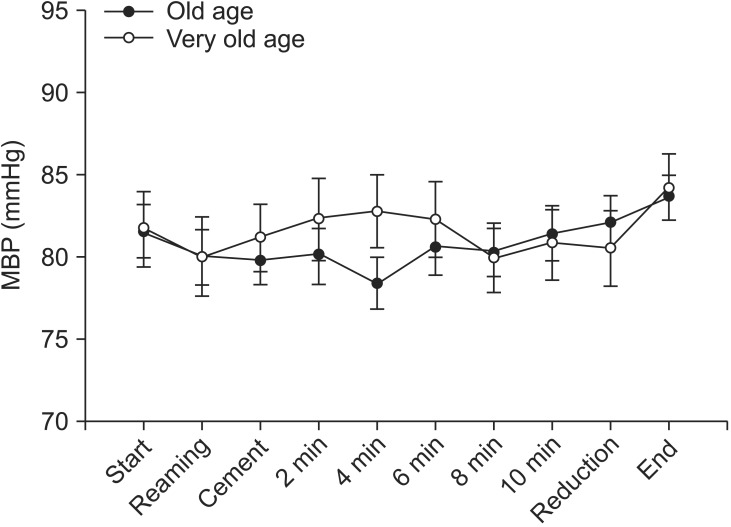

A total of 100 patients were enrolled in this study. Sixty-five patients in the old age group and 32 patients in the very old age group were suitable for the study. Three patients (2 in the very old age group and 1 in the old age group) were excluded due to BCIS requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The demographic data of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the old age group patients was 78.9 years, and that of the very old age group patients was 89.4 years. Most patients in the old age group were 75-80 years old, while the total patients ranged in age from 65 to 84 years old. In the very old age group, the number of patients over the age of years was 15, and the oldest patient was 98 years old, 160 cm, 41 kg, and female, with hypertension. Women outnumbered men at a 3 : 1 ratio in both groups. There was no significant difference in the frequency of preoperative coexisting disease except diabetes mellitus that was found in only 3 patients (9%) in the very old age group and in 22 patients (33%) in the old age group (Table 1). The range of sensory block levels that were checked 20 minutes after spinal anesthesia showed T8-T11 with no significant difference between the 2 groups.

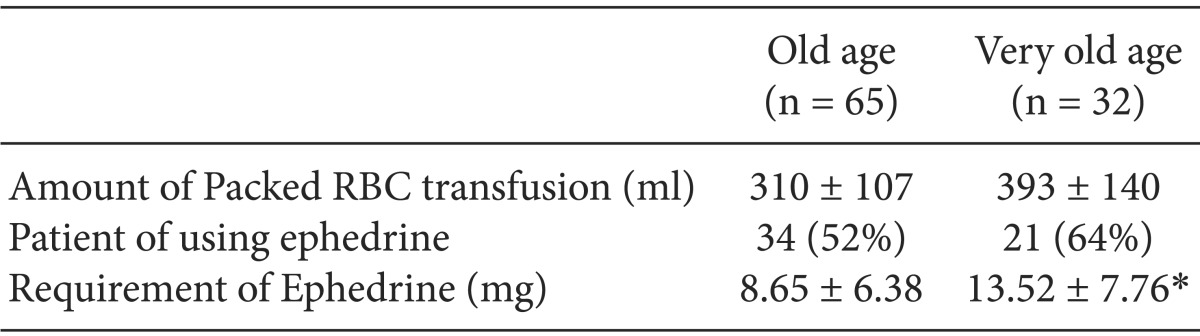

In the very old age group, cardiac index was significantly decreased compared to the old age group during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty (Fig. 1). The very old age group showed significantly lower cardiac indices at the time point of cement insertion, 10 minutes after cement insertion, and at the time point of femoral joint reduction compared to the starting time point of the operation, while the old age group showed lower cardiac indices at the time point of femoral canal reaming and 4 minutes after cement insertion compared to the the starting time point of the operation (Fig. 1). Cardiac index was decreased during the pericementation period in both groups. However, in the old age group cardiac index was immediately recovered and maintained until the end of the operation, while in the very old age group it was decreased until the end of the operation, without recovery to baseline.

Comparison of changes in cardiac index (CI) between the old age and very old age groups during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. Values are expressed as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared to the starting time point of the operation (Bonferroni corrected). Start: starting time point of the operation, Reaming: femur reaming, Cement: cement insertion, Reduction: femoral joint reduction, End: end of the operation. 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 min: time points.

Stroke volume was significantly lower in the very old age group than in the old age group during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. In the very old age group, stroke volume was significantly lower at the time point of cement insertion, 10 minutes after cement insertion, and at the time point of femoral joint reduction compared to the starting time point of the operation, while in the old age group, it was significantly lower only at 4 minutes after cement insertion compared to the starting time point of the operation (Fig. 2).

Comparison of changes in stroke volume (SV) between the old age and very old age groups during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. Values are expressed as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared to the starting time point of the operation (Bonferroni corrected). Start: starting time point of the operation, Reaming: femur reaming, Cement: cement insertion, Reduction: femoral joint reduction, End: end of the operation. 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 min: time points.

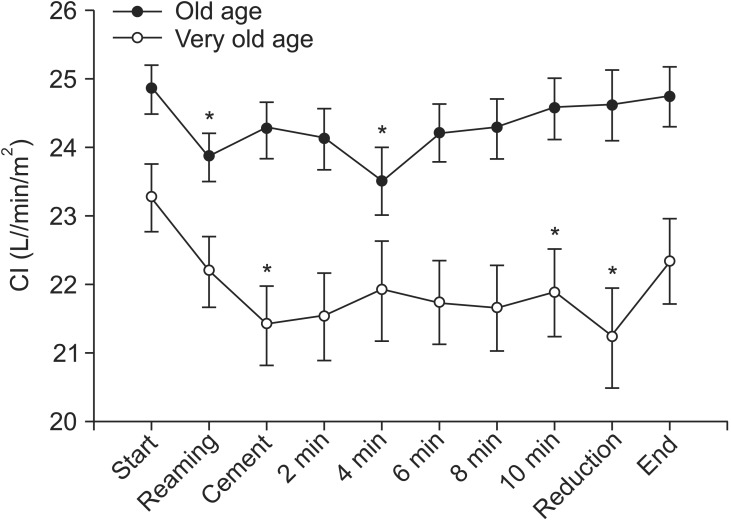

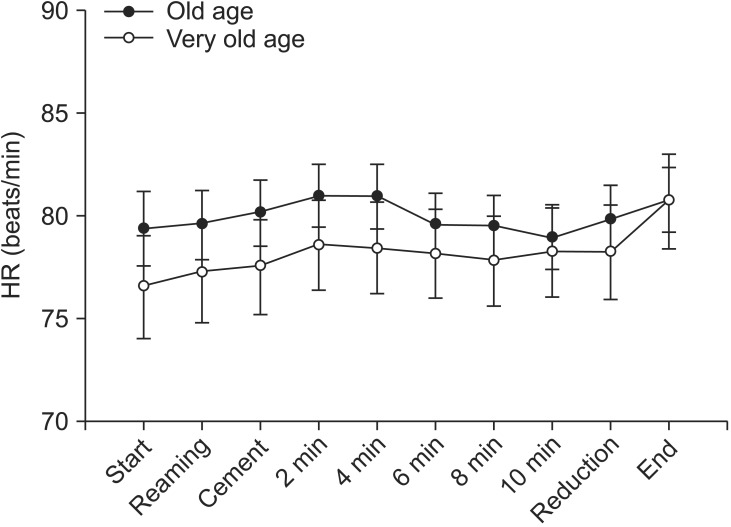

Mean blood pressure and heart rate showed no significant differences between the 2 groups during the cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. There were no significant differences in mean blood pressure and heart rate between the time point of each procedure and the starting time point of the operation within both groups (Figs. 3 and 4).

Comparison of changes in mean blood pressure (MBP) between the old age and very old age groups during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. Start: starting time point of the operation, Reaming: femur reaming, Cement: cement insertion, Reduction: femoral joint reduction, End: end of the operation. 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 min: time points.

Comparison of changes in heart rate (HR) between the old age and very old age groups during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. Start: starting time point of the operation, Reaming: femur reaming, Cement: cement insertion, Reduction: femoral joint reduction, End: end of the operation. 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 min: time points.

Two patients in the very old age group and 1 patient in the old age group underwent cardiopulmonary resuscitation with epinephrine and intubation. One patient in the very old age group had cardiac arrest and then underwent external cardiac massage, but finally died on the operative day. One patient in each group had severe hypotension and bradycardia and then received epinephrine injection (10-100 µg), fluid resuscitation, and intubation in the pericementation period. After resuscitation, the patients regained stable hemodynamic state.

The mean amount of packed red blood cells used during the operation was similar in the old age and very old age groups (310 vs 393 ml). To maintain hemodynamic stability during the operation, especially after cement insertion, the requirement of ephedrine was about 5 mg higher in the very old age group than in the old age group (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the very old age group had more significant hemodynamic changes compared to the old age group during cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. Cardiac index was significantly lower in the very old age group than in the old age group. After cement insertion, especially 10 minutes after cementing and femoral joint reduction, cardiac index was lower than the starting time point of the operation within the group. However, in the old age group, cardiac index was temporally decreased during the reaming of the femoral canal and 4 minutes after cement insertion, with a rapid recovery to baseline. Stroke volume also showed a significant decrease in the very old age group compared to the old age group. The reason for these differences is more decreased cardiac function associated with older age in the very old age group than in the old age group (78.9 vs 89.4 years).

Since complication rates from major surgery increase with age, comorbid illness and poor baseline functional status in the old age group can lead to higher risk of mortality and morbidity during anesthesia. A previous study demonstrated that the anesthesia-related mortality rate is 3 times higher in the very old subjects aged over 85 years than in the old subjects aged 65-84 years [10]. Despite the higher mortality and complication rates in the very old age group, there is still no standard method for safe anesthetic management. With increasing age, decreased beta-adrenergic responsiveness and increased incidences of conduction abnormalities cause hypertention and bradyarrythmia [11]. A noncompliant older heart is vulnerable to changes in ventricular preload and cardiac output [11]. In our study, the requirement of ephedrine, a vasopressor, to treat hypotension during operation was higher in the very old age group than in the old age group (13.52 vs 8.65 mg), which was probably due to the decline in cardiac index in the very old age group.

Fractures of the proximal femur mainly occur in the elderly due to osteoporosis, coexisting disease, and an increased incidence of trivial trauma [4]. Cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty is a viable treatment option for femur neck fracture, which yields good outcomes in terms of return to the prefracture level of activity and independent ambulation [5]. Even though the noncemented technique is used in hip arthroplasty, bone cement is still popularly used in most arthroplasty cases due to better implant survival [12]. Hazards of using bone cement for fixation in the procedure of bipolar hemiarthroplasty have been reported [6,13]. Symptoms, such as hypotension, hypoxia, cardiac arrhythmia, even cardiac arrest occur in the surgical procedure, which is known as BCIS [6,14]. Urban et al. [15] showed the presence of detectable intracardiac emboli during femoral arthroplasty by using transesophageal echocardiography. These emboli derived from bone marrow in the operative field can lead to increased pulmonary vascular resistance with right ventricular dysfunction and consequently decreased cardiac output, which usually occurs at the time points of femoral canal reaming, bone cement implantation, insertion of the prosthesis, and femoral joint reduction.

BCIS presents a wide range of severity. Many patients undergoing cemented arthroplasty reveal a significant but transient reduction in systemic blood pressure in relation to cement insertion [7,8]. We experienced 3 cases (2 in the very old age group and 1 in the old age group) of BCIS requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation during cemented hemiarthroplasty. One case of a 91-year-old female patient who had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, and dilated cardiomyopathy died 2 hours after cardiac arrest. Another case of a 90-year-old female patient who had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and mild dementia survived with cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The third case of an 80-year-old female patient who had a history of hypertension, diabetes, and Parkinson's disease also survived with cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Although many cases of BCIS have been described, neither its incidence of cardiac arrest nor mortality data has been reported. Donaldson et al. [14] reported that the intraoperative mortality rate of cemented hip arthroplasty is 0.11% (95% CIs: 0.07-0.15) based on 3 large cases reviews. Hamel et al. [11] documented that the 30-day mortality rate in hip arthroplasy differs according to age and emergency vs elective states. Our study showed a mortality rate of 1%. It should be noted that the mean age of our patients was older than those of previous studies and that the enrolled patients were small in number and had only fracture cases by trauma but not disease [16,17]. Intertrochanteric femur fracture is one of the significant risk factors for developing BCIS [14].

Early detection of the decline in cardiac function during pericementation is important in maintaining hemodynamic stability for geriatric patients with poor cardiovascular functional reserve. Previous studies demonstrated that cardiac output and stroke volume are more valuable for detecting hemodynamic changes than conventional noninvasive monitoring index [9, 15]. Our study showed that invasive monitoring using cardiac index and stroke volume was more sensitive to hemodynamic changes than noninvasive monitoring using mean blood pressure and heart rate.

The limitation of this study is that the double-blinded method was not used for data collection. Although we collected data prospectively, it was impossible for researcher to be blinded to patient age during the recording of data. Consequently, we could not avoid slection bias. Second, it is uncertain whether the significant decrease in cardiac index affected development of postoperative complications, such as myocardial infarction, respiratory failure, and 30-day mortality, in the very old age group. Further studies with a larger sample size are required to confirm our results.

In conclusion, it is suggested that very old patients (≥ 85 years) undergoing cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty due to intertrochanteric fracture may show more severe hemodynamic changes and require more administration of vasopressors to maintain hemodynamic stability. Careful hemodynamic monitoring and management are warranted in very old patients undergoing cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty.