The effect of aprepitant for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery with intravenous patient controlled analgesia using fentanyl: aprepitant plus ramosetron vs ramosetron alone

Article information

Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of an aprepitant, neurokinin-1(NK1) receptor antagonist, for reducing postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) for up to 24 hours in patients regarded as high risk undergoing gynecological surgery with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV PCA) using fentanyl.

Methods

In this randomized, open label, case-control study 84 gynecological surgical patients receiving a standardized general anesthesia were investigated. Patients were randomly allocated to receive aprepitant 80 mg P.O. approximately 2-3 hours before operation (aprepitant group) or none (control group). All patients received ramosetron 0.3 mg IV after induction of anesthesia. The incidence of PONV, severity of nausea, and use of rescue antiemetics were evaluated for up to 24 hours postoperatively.

Results

The incidence of nausea was significantly lower in the aprepitant group (50.0%) compared to the control group (80.9%) during the first 24 hours following surgery. The incidence of vomiting was significantly lower in the aprepitant group (4.7%) compared to the control group (42.8%) during the first 24 hours following surgery. In addition, the severity of nausea was less among those in the aprepitant group compared with the control group over a period of 24 hours post-surgery (P < 0.05). Use of rescue antiemetics was lower in the aprepitant group than in the control group during 24 hours postoperatively (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

In patients regarded as high risk undergoing gynecological surgery with IV PCA using fentanyl, the aprepitant plus ramosetron ware more effective than ramosetron alone to decrease the incidence of PONV, use of rescue antiemetics and nausea severity for up to 24 hours postoperatively.

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting are the most common complaints by patients after anesthesia. The phenomenon known as post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) has generated as much interest as post-operative pain experienced by patients [1]. PONV may occur after the onset of postoperative complications, including symptoms such as discomfort, pain, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, surgical wound dehiscence, hemorrhage, and aspiration pneumonia [2]. The prevalence rate of PONV is about 30%, but it however this rate fluctuates according to each patient, plus surgical and anesthetic factors. It may be as great as 80% or higher in patients with high-risk for PONV [3,4]. The Neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors which exist in the gastrointestinal vagal afferent and central nervous system vomiting reflex pathway generate conditions of nausea and vomiting due to activation by Substance P [5].

Aprepitant is a selective NK1 receptor antagonist. This antiemetic was approved for use by the FDA in 2003. Aprepitant has long half-life and has demonstrated efficacy against nausea and vomiting according to studies focused on chemotherapy (chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting, CINV) in combination other antiemetic drugs [6]. Also it has been reported to be effective in PONV prevention and was superior to ondansetron, particularly with regards to the antiemetic effect [7,8]. However, there is currently no research report about aprepitant use in PONV prevention among the Korean population.

Therefore, the aim of this research was to determine the efficacy of PONV prevention with aprepitant and subsequently compare the use of the aprepitant with ramosetron and ramosetron single injection in patients who were considered at high risk for PONV, gynecologic surgery receiving IV PCA using fentanyl in general anesthesia.

Materials and Methods

This research was carried out between April 10th and November 30th in 2011. After we obtained permission from the Institutional Review Board, we explained the details of this study and received written informed consent from all patients.

Eligible patients included 84 women between 20 and 70 years of age, with a physical status of I-II according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists, who were scheduled to undergo gynecological surgery with general anesthesia and received IV PCA.

Exclusion criteria included patient refusal to participate in the research, patients who had a history of drug abuse, hypersensitivity reaction, nausea and received antiemetics before surgery within 24 hours, pregnancy, breastfeeding status, cancer patients, inadequate participation in clinical trials due to other reasons.

According to computer-based random number generation, patients were divided into an aprepitant group (n = 42) and a control group (n = 42). Those in the aprepitant group were administered 80 mg aprepitant (Emend [R], Seoul, Korea, MSD) orally 2-3 hours before induction of anesthesia while the control group did not receive administration of any drug.

All patients received 0.2 mg glycopyrrolate IM as premedication 30 mins before the operation and when arriving at the operating room, standardized monitoring was initiated to include noninvasive blood pressure measuring equipment, electrocardiogram, and pulse oximeter.

Patients were induced with 2 mg/kg propofol intravenously. After the loss of consciousness, desflurane was used to maintain anesthesia that allowed for sufficient muscle relaxation using 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium implemented by endotracheal intubation.

In all patients, the ramosetron 0.3 mg (Nasea®, Astellas Pharma Korea Inc., Seoul, Korea) was administered intravenously after induction of anesthesia.

The maintenance of anesthesia was performed with 2 L/min O2 and N2O, 6-8 vol% desflurane, and 0.1-0.3 mcg/kg/min remifentanil. Additional doses of rocuronium were given when further muscle relaxation was necessary.

The end tidal partial pressure of carbon dioxide was maintained between 35 and 40 mmHg.

After the surgery, muscle relaxation was reversed by administering pyridostigmine and glycopyrrolate.

For postoperative pain control, IV patient controlled analgesia was used so that 1,500 mcg fentanyl was diluted with 70 ml saline solution and it was administered at a basic basal infusion rate of 1 ml/h, bolus 1 ml, and lockout time 6 minute.

In cases where nausea and vomiting were serious or the patient desired the treatment, 10 mg metoclopramide was administered. When necessary, 4 mg ondansetron was administrated as an additional treatment.

The patient's age, weight, surgery time, anesthesia time, past history of nausea, past history of PONV, smoking and amount of usage of remifentanil was recorded. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (Table 1).

In the recovery room, the anesthesiologist visited with each patient, being blinded to the conditions. The incidence of PONV, severity of nausea, use of rescue antiemetics, along with side effect such as dizziness and headache were evaluated.

The extent of nausea was assessed by a 5-point Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), in which patients rated nausea from none to intractable (none: no nausea, mild : mild nausea, moderate: moderate nausea, severe: severe nausea, and intractable: intolerable as well as vomiting).

PONV incidence was looked at in 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist single injection at approximately 70% [9,10], the absolute reduction rate was expected at 30% and the group per 42 people found the number of valid sample with aprepitant administration in the significance level of the power of 80% and with an alpha value of 0.05.

Analysis of data was performed using SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL., USA). The categorical data was analyze using the chi-square test and continuous data along with the Student's t-test.

In all analyses, statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

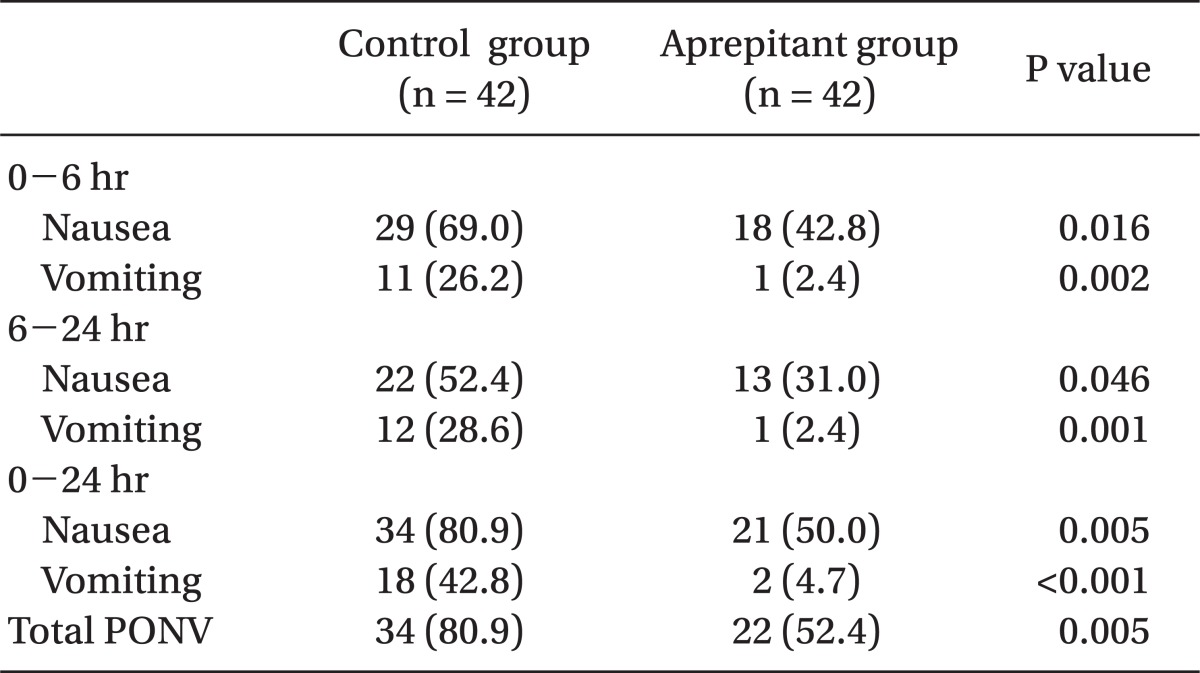

The incidence of PONV was significantly lower in the aprepitant group (52.4%) compared to the control group (80.9%) during the first 24 hours following surgery (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

The incidence of nausea was significantly lower in the aprepitant group (50.0%) compared to the control group (80.9%) during the first 24 hours following surgery, and there were significant differences in the incidence of vomiting between the two groups, evidenced by 42.8% in the control group and 4.7% in the aprepitant group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

The incidence of nausea was significantly lower among those within the aprepitant group (42.8%) relative to the control group (69.0%) during the first 6 hours following surgery, and the incidence of nausea was significantly lower in the aprepitant group (31.0%) compared to the control group (52.4%) during the 6-24 hours following surgery. There were significant differences in the incidence of vomiting between the two groups with 26.2% in the control group and 2.4% in the aprepitant group during the first 6 hours following surgery, and 28.6% in the control group and 2.4% in the aprepitant group during 6-24 hours following surgery (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

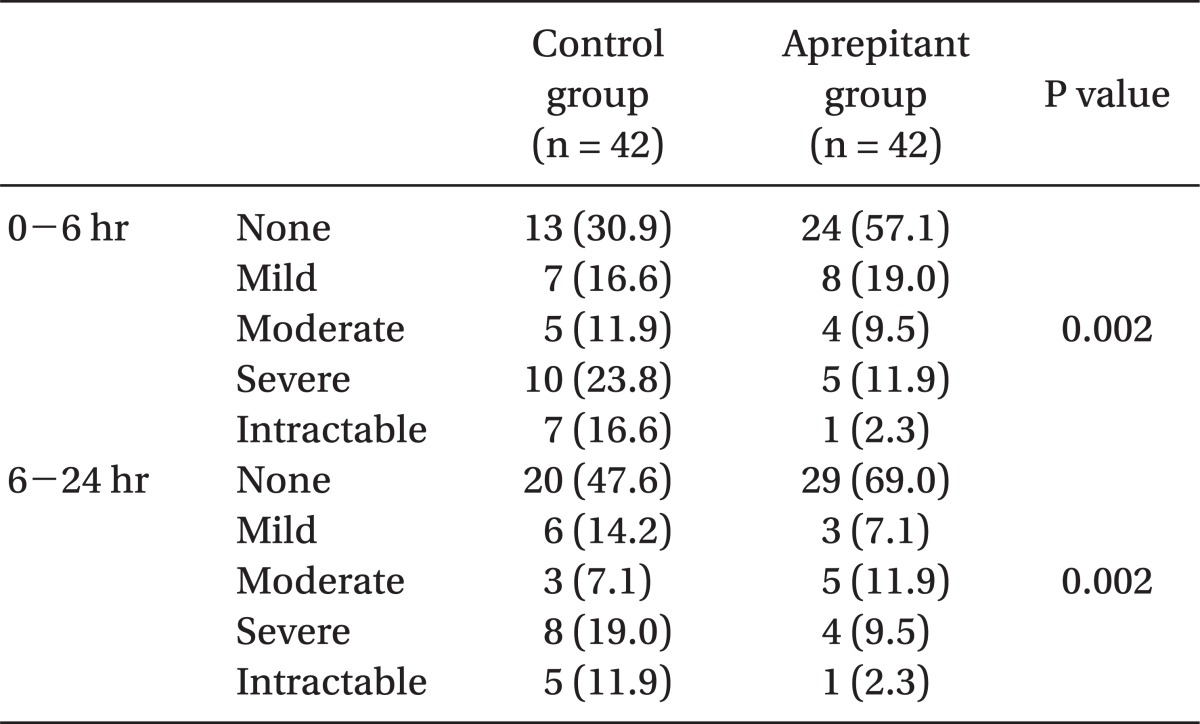

In addition, severity of nausea was less in the aprepitant group as compared with the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

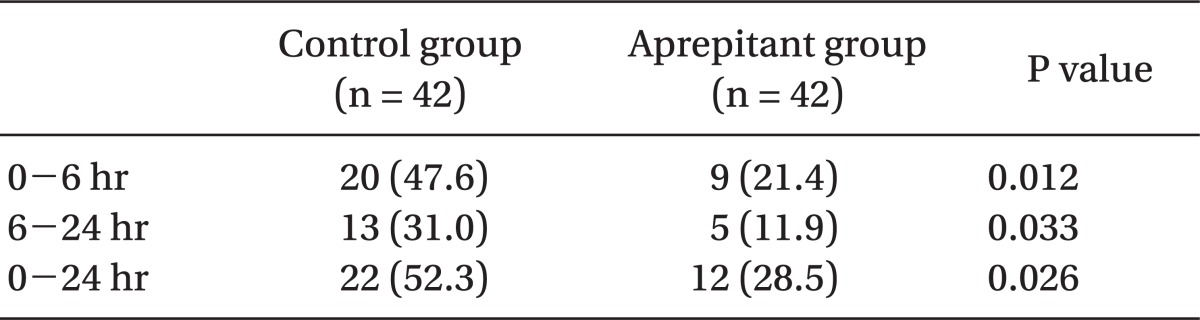

Use of rescue antiemetics was lower in the aprepitant group (28.5%) than in the control group (52.3%) for 24 hours postoperatively (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

There were no differences in the incidence of dizziness between the two groups as 23.8% in the control group and 19.0% in the aprepitant group were observed during 24 hours following surgery, and there were no differences in the incidence of headache between the two groups with 14.3% in the control group and 11.9% in the aprepitant group, and there were no differences in the incidence of sedation between the two groups as we observed 4.8% in the control group and 2.4% in the aprepitant group (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, results demonstrated that the use of combination therapy of 80 mg aprepitant oral administration and IV 0.3 mg ramosetron was lower in the incidence of nausea and vomiting than IV 0.3 mg ramosetron alone, particularly when the incidence of vomiting was expected to be markedly reduced.

Considering the patient's discomfort and a high incidence of PONV, many new drugs for prevention and treatment of PONV were developed and studied recently but there is no drug which fully prevents and effectively treats PONV [2,11].

Factors of nausea and vomiting after surgery are varied including patient's individual factors, surgical factors and anesthetic factors. Patient's individual factors in women include young age, obesity, past history of nausea and vomiting, motion sickness and surgical factors is otorhinolaryngologic surgery, breast surgery, strabismus surgery, gynecological surgery, and laparoscopic surgery while anesthetic factors include volatile anesthetics, nitrous oxide, narcotic analgesics, and long duration of aesthesia.

Among various predictors of PONV, Apfel et al. [3] described that independent predictive factors include gender, history of the motion sickness or PONV, lack of smoking habits and use of opioids after surgery. And if none, one, two, three, or four of these risk factors were present, the incidences of PONV were 10, 21, 39, 61, and 79%, respectively.

All patients in this study were considered high-risk with more than a rated 3 risk factor, including female gender, use of opioid for pain control, gynecological surgery and least 90% of patients were non-smokers.

In the past, the droperidol and selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists were most commonly used for PONV [12]. However, after the United States Food and Drug Administration warned that use of droperidol can cause serious arrhythmia in 2001, droperidol use is controversial and its production was interrupted in Korea [13,14]. Subsequently, serotonin receptor antagonists have been widely used for the prevention and treatment of PONV and CINV because there is low risk of side effects as compared with other antiemetics [12]. However, the incidence of PONV was reported as high as 30-40% in spite of this prevention and treatment.

In our observations, the incidence of PONV was higher than our expectation as 80% was seen in the control group which received ramosetron alone during 24 hours postoperatively.

However, Oh et al. [9] have shown that incidence of PONV was high as 67% in patients who were administered a ramosetron single injection under laparoscopic operation during the first 12 hours after surgery. Kim et al. [10] showed that the incidence of PONV was each 70.7% and 66.7% in the patients who were administered other serotonin antagonists such as ondansetron, dolasetron receiving IV PCA after mastectomy during the first 24 hours postoperatively.

Even with administration of ramosetron, the incidence of PONV has been high. This may be due to the influence of nitrous oxide in combination with remifentanil. Thus, we were able to determine that the patients who received IV-PCA using opioids in the high risk group of PONV needed combination therapy with other several antiemetic drugs rather than the antiemetic drug single injection through our study.

Henzi et al. [15] found that the combination of serotonin receptor antagonist with dexamethasone decreased the risk of PONV, and Khalil et al. [16] found that the combination of serotonin receptor antagonist with promethazine decreased the incidence and severity of PONV.

Aprepitant has been involved in numerous studies in the area of CINV, there are currently many studies that have reported on aprepitant use for PONV [8,17]. Antiemetic effect of aprepitant results from blocking the binding of substance P which is known to be related to delayed vomiting at the NK1 receptor [18]. The NK1 receptor antagonist was shown to act in both the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system [19-21].

However, there has not yet been a study for domestic patients, and this study will be used as a starting point in the clinical application of aprepitant, as it focused in particular on high-risk patients of PONV with gynecologic patients.

Diemunsch et al. [22] stated that the efficacy of aprepitant was superior to ondansetron. Gan et al. [7] stated that aprepitant and ondansetron are similar in their effect on nausea reduction, but prevention of vomiting of aprepitant was better than that of ondansetron in the study comparing aprepitant versus ondansetron. Recently, Vallejo et al. [23] stated that the addition of aprepitant to ondansetron significantly decreased postoperative vomiting rates and nausea severity for up to 48 hours postoperatively, in patients undergoing plastic surgery.

We observed that the incidence of nausea was reduced statistically significantly by 50% in the aprepitant group compared to 80.9% in the control group and the incidence of vomiting reduced significantly to 4.7% in aprepitant group compared to 42.8% in the control group for 24 hours. Relative reduction rate of nausea was 38% whereas relative reduction rate of vomiting was 89%. This suggests that anti-vomiting effect is excellent compared with the anti-nausea effect of aprepitant. This result is similar to those found in a previous study with a 80% relative reduction rate of vomiting with a novel, neurokonin-1 antagonist, cp-122,721, compared to placebo, as reported by Gesztesi et al. [24].

The strong anti-vomiting effect of aprepitant is very useful when vomiting occurs and creates dangerous complications, such as in neurosurgery or jaw-wiring incidents.

Gan et al. [7] stated that the aprepitant was more effective than ondansetron in vomiting prevention but it did not show any difference between 40 mg and 125 mg in terms of the dose of the aprepitant in the study, while Kakuta et al. [17] suggested that aprepitant can effectively lower PONV and also hasten recovery in gynecological laparoscopic surgery comparing aprepitant 80 mg with placebo.

In addition, the aprepitant 80 mg was used in this research because the product on the market in Korea was only available in 2 doses, 80 mg and 120 mg.

Headache, dizziness are the most common known side effects of selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists.

In our research, 8 patients (19%) in the aprepitant group and 10 patients (23.8%) in the control group experienced dizziness and headache occurred in 6 patients (14.3%) in the control group and 5 patients (11.9%) in aprepitant group but because there was no difference between 2 groups statistically, the headache did not seem to affect the overall clinical conditions of the patients.

Limitations of this study included the fact that placebo and aprepitant groups could not be directly compared. However, as there was an ethical issue as all patients of within the study were high-risk subjects, ramosetron was administered to all patients within both groups.

In conclusion, in patients regarded as high risk undergoing gynecological surgery with IV PCA using fentanyl, 80 mg aprepitant plus 0.3 mg ramosetron reduced the incidence of PONV, use of rescue antiemetics and nausea severity as compared to 0.3 mg ramosetron alone for up to 24 hours post-operatively to be significant.

Further research is needed to compare the efficacy of serotonin receptor antagonists and aprepitant as well as the combination of other antiemetic drugs in the prevention and treatment of PONV.