Misdiagnosis of pneumothorax by ultrasonography after central venous catheterization in a patient with pleural adhesion

Article information

Performing central venous catheterization (CVC) under ultrasound guidance may be required to reduce the risk of pneumothorax (PNx), and ultrasonographic signs of pleural movement (e.g. lung sliding and lung point signs) can be useful for the bedside detection of PNx immediately after CVC placement [1]. However, although the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonographic signs are sufficient for the diagnosis of PNx, similar findings can be found in patients with lung fibrosis or pleural adhesion without PNx. We here report on a patient suspected of having a PNx after CVC insertion which was finally revealed to be related to an underlying pleural adhesion.

A 76-year-old male patient (height: 160 cm; weight: 46 kg) was scheduled for a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD). He had a medical history of well-controlled hypertension and pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) that had been cured 10 years prior. Additionally, he had a 30 pack-year smoking history. Preoperative chest radiography and computed tomography of the chest (chest CT) revealed sequelae of pulmonary TB, multiple bullae, and centrilobular emphysema in both lungs. The preoperative pulmonary function test showed a mild restrictive pattern. The patient did not complain of dyspnea or any physical limitation in daily activities. All other preoperative laboratory findings were within the normal range. No preoperative medication was prescribed.

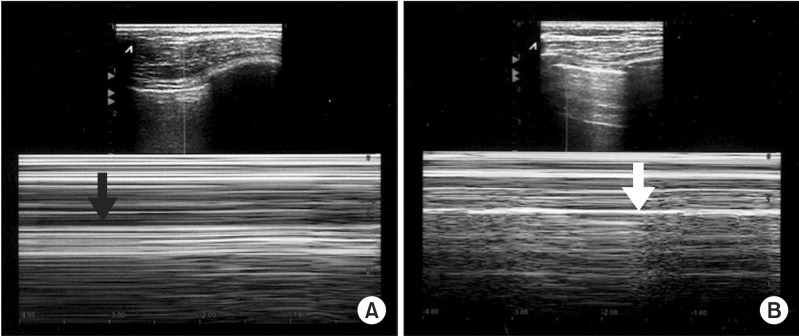

Anesthesia was induced with intravenous propofol and maintained with a 1-1.5 vol% of sevoflurane combined with a target-controlled infusion of remifentanil. Vecuronium was used to facilitate orotracheal intubation. After intubation, CVC was performed via the right internal jugular vein under ultrasound guidance (E-cube Inno; Alpinion Medical Systems, Seoul, Korea). After successful catheterization, the normal to-and-fro movement of the pleural line (the lung sliding sign) was absent at the right third intercostal space (ICS) (Fig. 1A), but present at the left third ICS. The sonography probe was moved downward to observe the ultrasonography pattern changing from normal to that of a PNx with the synchronization of regular respiratory movement (the lung point sign) at the fourth ICS (Fig. 1B).

(A) Ultrasonographic findings at the right third ICS. Upper, real-time mode. Lower, time-motion mode. The normal homogenous granular pattern generated by the lung sliding over the motionless parietal pleura (the lung sliding sign) is not seen below the normal horizontal lines representing the static chest wall, which is reminiscent of a barcode (the barcode sign, black arrow). (B) Ultrasonographic findings at the right fourth ICS. Upper, real-time mode. Lower, time-motion mode. A change of the ultrasonographic pattern from the normal granular pattern to the PNx pattern, coupled with respiratory movement, was observed (the lung point sign, white arrow).

An immediately obtained portable plain chest radiography showed no interval change compared with that of the preoperative period. Although the ultrasonographic signs suggested PNx, there were no clinically significant changes, such as a unilateral decreased breathing sound by chest auscultation, a change in the capnography pattern, a change in peak airway pressure, or a change in the end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) concentration. Arterial blood gas analysis showed no abnormal findings. It was suspected that a certain limitation in pleural movement, such as pleural adhesion, was responsible for the abnormal ultrasonographic signs. The operation proceeded without any significant hemodynamic or respiratory changes. The patient was fully awake and transferred to the recovery room after extubation. No respiratory distress signs were observed in the recovery room. On postoperative day 1, the chest CT was repeated by a radiology specialist and showed pleural adhesion from the first to the fourth ICS.

Ultrasonographic findings, such as the lung sliding, lung point, and A line signs, are used for the diagnosis of PNx [1]. The lung sliding sign is a to-and-fro movement visible at the pleural line that is synchronized with breathing movements. The lung point sign, which is an all-or-nothing sign, is a change from the normal sonographic pattern to the PNx pattern. In our present case, the patient was at increased risk of PNx after CVC placement. The noted absence of lung sliding and the presence of lung point signs at the right fourth ICS were initially interpreted as a right-sided PNx after CVC. However, the absence of any clinical signs and a normal chest radiography obtained immediately after CVC made it difficult to diagnose PNx. The chest CT finding corresponded with the ultrasonographic findings of the operating room. Therefore, we were able to exclude PNx after CVC and explain the abnormal and false-positive ultrasonographic signs (limitation of pleural movement) as being due to pleural adhesion.

Although absence of the lung sliding sign combined with presence of the lung point sign is useful for diagnosing PNx, the sliding sign may be absent without PNx in patients who have other clinical conditions [1-3] and it is reported to be useful for detecting pleural adhesion in patients undergoing surgical thoracic intervention [4]. Also, the presence of the lung point sign was reported without evidence of PNx in a chest CT in a patient who had multiple right rib fractures (the "pseudo-lung point" sign) [5].

In the present case, ultrasonographic chest evaluation before CVC may have been helpful in distinguishing the confounding ultrasonographic findings of pleural adhesion from those of PNx. However, pleural adhesion was not suspected because the patient did not complain of any respiratory symptoms, in spite of his medical history, and there was no comment about the pleural adhesion on the chest CT and plain chest radiography evaluations. Because PNx is a common but potentially serious complication after CVC, early detection of PNx using ultrasonography at the bedside could be effective in preventing serious complications with a high sensitivity and specificity. However, abnormal ultrasonographic findings should not be regarded as definite signs of PNx in patients with chronic lung disease, but should be carefully considered with other clinical data in order to confirm or reject PNx diagnosis.