Subclavian artery perforation and hemothorax after right internal jugular vein catheterization

Article information

Internal jugular vein (IJV) catheterization is a common practice in the operating room for perioperative management. However, many complications associated with IJV catheterization has been reported such as adjoining arterial puncture and if subclavian arterial puncture occurs during IJV catheterization, it can be a life-threatening complication [1].

A 19 kg, 122 cm, 7-year-old Vietnamese boy with a known ventricular septal defect (VSD) was admitted for surgical intervention. A preoperative echocardiogram revealed small sized perimembranous type VSD with a left to right shunt. A chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly with increased pulmonary vasculature and an EKG showed left axis deviation. The peripheral blood test results were: Hemoglobin (Hb) 15.0 g/dl, Hematocrit 43%, platelet 374,000/µl. Upon arrival in the operating room, the patient's blood pressure was 105/80 mmHg, pulse rate was 112 beats/min, and SpO2 was 100%. For anesthetic induction, propofol 40 mg and rocuronium 20 mg were intravenously administered and an endotracheal intubation with a 5.5 mm tube was performed. After induction of general anesthesia, the patient was positioned for right internal jugular vein catheterization. He was laid in a supine position with his head turned to the left. After identifying the triangle made by the sternal clavicular bellies of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the clavicle, the 22-gauge fine needle was intended at the lateral edge of the sternal belly of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and punctured the internal jugular vein. Dark non pulsatile venous blood was aspirated. But as we inserted an 18-gauge introducer needle to the same site, fresh pulsatile arterial blood was aspirated and the puncture site had swollen up. The needle was withdrawn and the puncture site was pressed for over 5 minutes. The next attempt to the same site was successful and a central venous catheter (7 Fr Three-lumen Central Catheterization Set with Arrowgard Blue, Arrow international Inc., PA, USA) was inserted to the right internal jugular vein. Before cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), central venous pressure was 7-8 mmHg and well preserved. However, blood pressure continuously decreased during CPB, and did not respond to the administration of fluid and inotrophic agent. We maintained blood pressure until the CPB and during the first one hour of CPB, mean arterial pressure was 40 mmHg. Approximately 2 hours after central venous catheterization, in the CPB state, the mean arterial pressure dropped to 35 mmHg and Hb was 5.8 g/dl. Inotropic agents were started immediately: dobutamine infusion rate was 10 µg/kg/hr, norepinephrine infusion rate was 0.1 µg/kg/hr and epinephrine infusion rate was 0.1 µg/kg/hr. At that time we noticed that the right pleura side of the patient was bulging, suggesting a hemothorax. Surgeons opened the right pleura and found huge clots and fresh blood filled the entire chest. After removal of the clots, the operator noticed that blood was pumping from the right apical chest wall with surrounding tissue hematoma. Full sternotomy was done to expose the right chest apical portion and a right subclavian arterial rupture near the brachiocephalic trunk was found. It was directly repaired and 3 units of packed red blood cells were infused. The patient's systolic blood pressure rose to 100 mmHg and all inotropic agents were discontinued. After insertion of a mediastinal and pleural drainage, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit in a stable condition (Fig. 1). Extubation was done on that day and mediastinal drainage was removed 3 days after and pleural drainage was removed 7 days after the operation. The patient was fully recovered and return to Vietnam after 1 month.

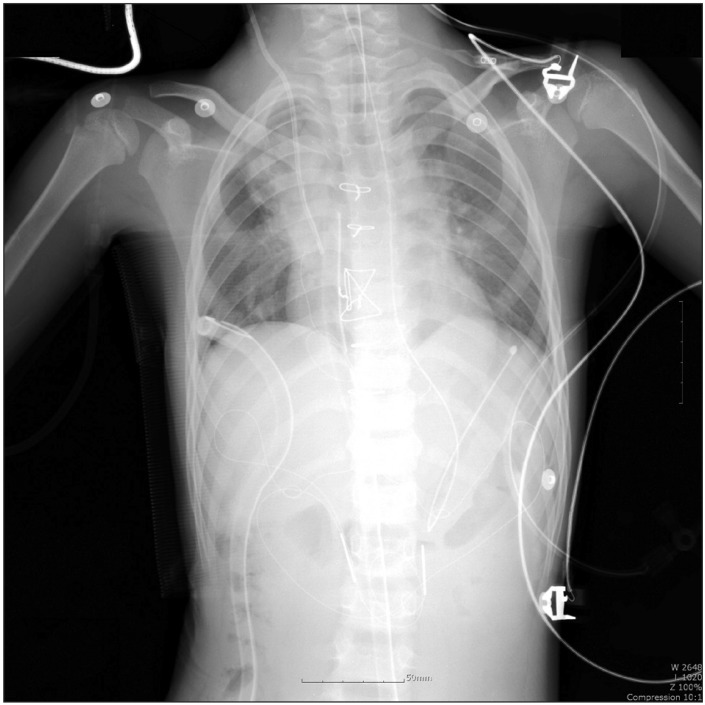

Central venous catheter, mediastinal drainage tube and right chest tube was in normal position in the chest radiograph. Some consolidation at the right upper perihilar area was observed.

Arterial puncture was the most commonly observed complication of central venous catheterization in children and its rate was approximately 8.9% [2]. Bagwell et al. [3] reported that this complication appeared to be more common in children aged 1 to 6 years, and 18 in 19 cases of hemothorax occurred after a percutaneous stick of the vessel. The most common arterial injury associated with IJV catheterization is carotid artery puncture and most are asymptomatic. Subclavian arterial perforation is less common but can cause lethal complications. According to other reports, roughly 1,500-2,000 ml of massive bleeding was observed and it was sometimes lethal [1,4]. 2 out of 6 children who had a subclavian arterial injury died from massive bleeding of about 800 to 1,400 ml [3]. All reported subclavian arterial puncture occurred at the right IJV catheterization, and the puncture site was close to the innominate artery [1,4]. In our case, like another case, a right subclavian arterial injury was observed. Kulvatunyou et al. [1] described an anatomical explanation for this complication; because of the specific anatomical feature of the right IJV and the subclavian artery, the right subclavian artery was liable to be injured during right IJV catheterization. This is because the branches of the right subclavian artery form the brachiocephalic trunk medial and posterior to the IJV, and the proximal portion of the right subclavian artery and IJV are overlapped. During IJV catheterization, if the introducer needle is inserted into the IJV too deeply, the needle could pass through the IJV wall at the overlapped area and possibly injure the adjoining right subclavian artery. This explains well why reported cases including ours have a typical location of the injury at the proximal portion of the right subclavian artery. Kuluatunyou called it the 'right sided phenomenon' and if the triad of acute hypotension, right-sided IJV cannulation, and chest radiographic evidence of hemothorax occurred, right subclavian arterial injury should be considered. Since most cases of hemothorax occurred after percutaneous stick in children, the site of insertion should be chosen carefully. In order to prevent subclavian arterial perforation, the needle insertion should start close to the apex of the two heads regarding the sternocleidomastoid muscle or at least 3-5 cm above the clavicular head. Ultrasound guidance is occasionally used for the safe puncturing of the venous and arterial structure [5]. In conclusion, perforation of the subclavian artery during IJV catheterization can be a lethal complication, so it is important to understand the association between right-sided IJV catheterization and subclavian arterial perforation. If acute hypotension and chest radiographic evidence of a hemothorax occurs, the anesthesiologist must consider the possibility of subclavian arterial injury, especially during or after right IJV catheterization.