Cardiac arrest with pulmonary edema in a non-parturient after ergonovine administration recovered with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation -A case report-

Article information

Abstract

Ergonovine have been used for the prevention and treatment of postpartum or postabortion hemorrhage. Although this modality has been considered relatively safe in the obstetric patients, there were a few cardiac events associated with this drug in the post-delivery or post-abortion patients, especially in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. We experienced cardiac arrest in a non-parturient with no discernible risk factors. Although resuscitated, she also suffered from pulmonary edema with unstable hemodynamics and low oxygenation. To manage the patient, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was used and she recovered successfully without cardiopulmonary complications. Therefore, we recommend that when ergonovine is chosen as a modality, special caution should be paid to the pulmonary events, as well as cardiac, especially when administered by intravenously even in patients with no cardiovascular risk factors. If cardiac events occur, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or other measures, such as intra-aortic balloon pump can be helpful when conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation is not effective.

Ergonovine, an ergot alkaloid commonly used for the prevention and treatment of postpartum or post-abortion hemorrhage, which usually produces mild hypertension and no significant electrocardiographic change [1]. Even some parturient might complain of chest symptoms, it usually does not progress to the myocardial ischemia [2]. Although ergonvine have been considered relatively safe and used widely in the routine obstetric practice, there are a few serious adverse events with this drug, mostly after delivery or abortion [3-8], including disastrous results [3,4]. Most of them were initially presented with cardiac abnormalities [3,4,6-8], some heralded with pulmonary sign and symptoms before a cardiac event [5], and some with cardiovascular risk factors [3,4,7,8].

We experienced a non-parturient patient with no discernable cardiovascular risk factors, who suffered from sudden cardiac arrest, complicated with pulmonary edema, just after intravenous ergonovine injection. Although rescued from the cardiac arrest, she developed pulmonary edema with unstable hemodynamics and oxygenation. Therefore, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was used to support her cardiopulmonary system. She was successfully weaned from the support and recovered thereafter.

Case Report

A 31-year-old woman with height of 164 cm and weight of 42 kg (BMI; 15.62, normal; 18.5-23) was admitted for hysteroscopic myomectomy, under general anesthesia. Except penicillin allergy, she had no history of cardiovascular diseases, nor did she have any coronary risk factors, including smoking, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coagulative disorder, oral contraceptive use, and/or family history of myocardial disease. Physical examination and routine preoperative laboratory tests, including chest X-ray, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were unremarkable with total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein within normal range.

After arriving at the operating room, ECG, pulse oximetry, non-invasive blood pressure, and end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) monitoring were attached to the patient. For induction of general anesthesia, thiopental sodium 200 mg, followed by rocuronium 20 mg, were injected intravenously and classic laryngeal mask airway (No. 4) was inserted. Then, she was positioned to lithotomy for the operation. Anesthesia was maintained with desflurane 5.0-6.0 vol% in 50% nitrous oxide and oxygen. The operation was uneventful for 30 minutes, with stable vital signs, except slight tachycardia with heart rate 105 to 120 beats/min. Further, the estimated blood loss was negligible.

At the end of the surgery, ergonovine maleate 0.2 mg distilled with normal saline 10 ml was intravenously administered slowly for a minute at the request of the surgeon for the uterine contraction. About 2 minutes later, EtCO2 suddenly decreased to 20 mmHg from 33 mmHg, followed by a loss of plethysmographic wave. The patient was cyanotic, but anesthetic monitor showed no noticeable change in the airway pressure and expiratory tidal volume. The blood pressure, although measured at 119/89 mmHg a few minutes ago, was not checkable with un-palpable radial pulse, and ECG showed severe bradycardia, followed by asystole.

Immediately, 1 mg epinephrine was injected intravenously, FiO2 increased to 100%, and thereafter, chest compression was started. Laryngeal mask airway was changed to endotracheal tube (No. 7), under direct laryngoscopy, right internal jugular vein cannulated and arterial line in the right radial artery established, while chest compression continued, inotropics infused and intermittent atropine and other drugs were administered. Even with these measures, the patient responded poorly and cardiac rhythm couldn't be detected. The patient was just showing low blood pressure of about 40/20 mmHg, which was observed via arterial line, probably due to chest compression. About 20 minutes after cardiac arrest, ECG returned to sinus rhythm but with tachycardia and ST elevation. Blood pressure increased to 60/20 mmHg, heart rate was at 130 beats/min, SpO2 85%, and arterial blood gas analysis with pH 7.2, PCO2 42.7 mmHg, PO2 54.3 mmHg, bicarbonate 18.2 mmol/L, base -8.2 mmol/L, and sO2 82%. Other hematologic and electrolyte were within normal limits and the results were as follows: Hemoglobin 12.2 g/dl, Hematocrit 39.7%, Na+ 136 mmol/L, K+ 3.1 mmol/L, Ca2+ 4.5 mg/dl, and Cl- 117 mg/dl. With continued intotropic support, nitroglycerin 100 µg was intravenously administered with the suspicion of myocardial ischemia. Within 5 minutes, blood pressure further increased to 123/80 mmHg, heart rate to 128 beats/min, SpO2 100%. However, afterwards, the systolic blood pressure decreased to 75 mmHg and SpO2 88% again, despite inotropic support.

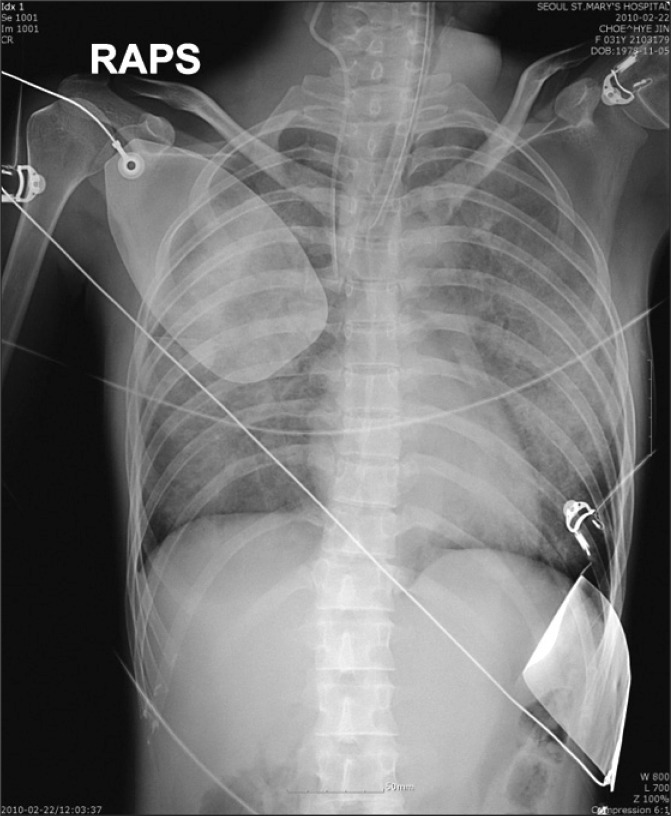

Chest X-ray, taken immediately after arrival to the intensive care unit, showed bilateral diffuse pulmonary edema (Fig. 1). Even though ECG didn't show definite ST abnormalities, except sinus tachycardia (Fig. 2), cardiac enzymes were elevated as follows; troponin I 3.2 ng/ml (normal < 0.78), CK-MB 12.08 ng/ml (normal < 5). Transthoracic echocardiography showed the ejection fraction of only 22% (normal 56-78%), with severe hypokinesia in the inferior and septal area. Patient was unresponsive, blood pressure still low with systolic pressure below 80 mmHg and oxygen saturation around 75-82%. So, the patient was managed with the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (Capiox SP Pump controller 101, Terumo, Japan) through left femoral veno-right femoral arterial route with initial blood flow of 2-2.5 L/min. After that, the hemodynamics and oxygenation became stable with blood pressure 100/47 mmHg, and SpO2 100%.

Electrocardiography taken just after the arrival of intensive care unit represents sinus tachycardia.

She regained consciousness at the night of the operative day, and endotracheal tube was removed the following day. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was weaned and inotrope infusion was stopped at the third postoperative day. Afterwards, she recovered and was discharged without cardiopulmonary complication.

Discussion

Ergonovine was known to control blood loss in the obstetric patients and even reduced the postoperative endometritis [9], making it useful for the prevention and treatment of postpartum or post-abortion hemorrhage. In addition, it can be used for the prevention of cluster headaches [10], and even relieving postdural puncture headaches [11]. Furthermore, it can provoke coronary spasm in patients with angina pectoris, so these characteristics are used to for the diagnosis of isolated spontaneous angina pectoris, especially those with Prinzmental's variant angina, patients with angina both at rest and at effort, and in patients with myocardial infarction and normal or nearly normal coronary arteries [12].

Although rare, the complications of ergonovine, usually in obstetric patients, occurred with intravenous [3,5,6], intramuscular [7], and even oral administration [8]. Among them, intravenous injection might cause rapid deterioration of hemodynamic variables, especially with high dosage. Surprisingly, there's only a case found to have immediate cardiac arrest detected, upon initial intravenous injection of ergonovine [6] as in this case, while one detected somewhat later with catastrophic result [3], and one even with repeated high dose [5].

In one case, cardiac sign was preceded by pulmonary edema a day before. However, they initially attributed it to blood transfusion and fluid overload, rather than considering ergonovine as the cause, because the placenat increta and uterine atony, which resulted in massive bleeding that further, required more transfusion. In addition, they continued to use ergonovine until cardiac events occurred [5]. In contrast, we noticed pulmonary edema just after the resuscitation, and even the fluid was not so much infused, which suggested pulmonary edema as the side effect of ergonovine. In other hands, the absorption of irrigation fluid might be considered as the cause of this incident, like in case of transurethral resection of prostate syndrome (TURP syndrome). But, in this patient, normal saline was used as the irrigation solution and the electrolyte values lied within normal range. So, we considered this possibility to be less likely.

Although some have cardiovascular risk factors [3,4,7,8], that's not true for all patient [5,6] as in this particular patient. In fact, in survivors of sudden cardiac arrest, ergonovine test can detect coronary spasm in patients without identifiable underlying heart disease [13].

The management of the cardiac events occurred from ergonovine may be difficult, and routine cardiopulmonary resuscitation sometimes inadequate [3,4] requiring additional aggressive measures, such as intraaortic balloon pump [5,6], intracoronary nitroglycerin [6], percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [7] or even extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [5]. Although her heart beat was restored with resuscitation, we needed more intervention to manage the patient. Perhaps coronary intervention might help the patient, however, we thought at that time the patient condition was not acceptable to that procedure. Furthermore, the patient had pulmonary problems, as well as cardiac. So we chose extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as the management tool and we thought it would help the patient recover from the cardiac and pulmonary insults.

The extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is an ideal short term circulatory support for critical patients, especially in emergency situations. It is used for the patients who experiences cardiogenic shock and/or pulmonary dysfunction that is unresponsive to conventional treatments and the patients who otherwise could not be weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass [14], usually veno-arterial configuration for cardiogenic shock, and veno-venous for respiratory failure [15].

In conclusion, ergonovine should be used with caution even in patients with no discernible cardiac risk factors. When cardiac complication occurs, it'd be better to consider the possibility of pulmonary edema, too. If cardiopulmonary stability might not be achieved, aggressive intervention like extracorporeal membrane oxygenation should be instituted to save the life.