Left atrial appendage thrombus detected by intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in a patient with acute small bowel infarction -A case report-

Article information

Abstract

Acute mesenteric ischemia and infarction is an emergent situation associated with high mortality, commonly due to emboli or thrombosis of the mesenteric arteries. Embolism to the mesenteric arteries is most frequently due to a dislodged thrombus from the left atrium, left ventricle, or cardiac valves. We report a case of 70-year-old female patient with an acute small bowel infarction due to a mesenteric artery embolism dislodged from a left atrial appendage detected by intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography and followed by anticoagulation therapy.

Mesenteric ischemia is due to hypoperfusion of bowel caused by a blockage of mesenteric blood flow, an angiospasm, or a low systemic blood pressure, which can lead to peritonitis, sepsis, bowel infarction, and even death. Therefore once suspected, immediate diagnosis and treatment is strongly required [1]. The authors discovered a small bowel infarction during an elective operation of right ovarian cyst and acute appendicitis in a patient with congestive heart failure with atrial fibrillation (AF). Based on her past medical history, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was immediately inserted. A thrombus was detected in a left atrial appendage (LAA) which was followed by a segmental resection and anastomosis of a small bowel and an anticoagulation therapy.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman (height: 156 cm, body weight: 48 kg) with lower abdominal pain was admitted and associated symptoms were fever, nausea, vomiting and diaphoresis which started from the day previous to her admission. On abdominal computed tomography (CT), right ovarian cyst in size of 2.5 cm was found, and an acute appendicitis was diagnosed by an abdominal ultrasonography. An elective operation was scheduled under the collaboration of gynecology and general surgery.

In the patient's past medical history, she had taken digoxin, dilatrend, nitrate, telmisartan, and thiazide for 5 years because of hypertension, congestive heart failure, AF, and right coronary artery 90% stenosis on coronary angiography. An electrocardiogram before operation showed AF with ventricular response 90-100 times/min, left ventricular hypertrophy. Cardiomegaly and pleural effusion were found on chest X-ray. On transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), ejection fraction was 55% and left atrial enlargement, right atrial enlargement and eccentric hypertrophy with decreased mobility of the inferior wall of the left ventricle were shown. A moderate aortic valve insufficiency, aortic valve sclerosis, mild aortic stenosis, and severe posterior mitral valve leaflet calcification were also found and the width of mitral valve measured by pressure half-time was 1.92 cm2. A chronic cerebral infarction in the right posterior cerebral artery was found on brain CT with symptoms of dysarthria. Signs of dehydration on physical examinations with prerenal azotemia of FeNa 0.1% and serum creatinine of 1.7 mg/dl on blood test led us to start an fluid therapy. The serum creatinine was decreased to 1.3 mg/dl after the fluid therapy.

Glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg IM was premedicated at 30 minutes pre-operation. The patient's blood pressure (BP) was 130/50 mmHg, ventricular response 90-100 times/min, and arterial oxygen saturation 97% when she arrived at the operation room. A right radial artery was cannulated with great caution before the induction of anesthesia. The induction of anesthesia was initiated with injecting 2 ml of 2% lidocaine to reduce injection pain and propofol (Diprivan® AstraZeneca, UK) and remifentanil (Ultiva® GlaxoSmithKline, UK) were injected using a target-controlled infuser (Orchestra® Fresenius Vial, France). After confirming the patient's being unconscious, rocuronium 40 mg was injected and then endotracheal intubation was performed with close monitoring of arterial blood pressure. Ventilation with 100% O2 was given while central venous catheterization was placed in right jugular vein. After the induction of anesthesia, the patient's vital sign showed no hemodynamic disorder with systolic BP 130-150 mmHg, diastolic BP 40-60 mmHg, ventricular response approximately 100-110 times/min, and central venous pressure (CVP) 8-9 mmHg. The effect site concentration was injected as 2.5-3.0 µg/ml of propofol and and 2.0 ng/ml of remifentanil.

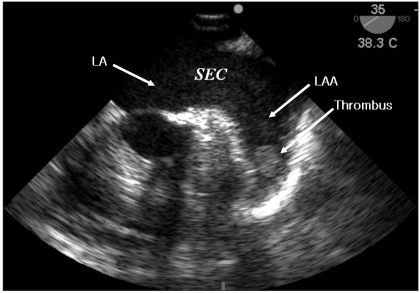

After the lower abdomen laparotomy at obstetrics and gynecology for the right ovary cystectomy, a small bowel infarction from jejunum to ileum was detected. The authors suspected a mesenteric arterial embolism based on the patient's previous medical history. A transesophageal echocardiology (SonoSite MicroMaxx, Bothell, USA) probe was immediately inserted and a spontaneous echo contrast (SEC or "smoke") in the left atrium (LA) and a 13 × 18 mm size thrombus in the LAA was detected (Fig. 1). The findings in TEE made a mesenteric arterial embolism highly suspicious for the cause of the small bowel infarction. A segmental resection and intestinal anastomosis were performed by the department of general surgery. No hemodynamic instability was observed through whole procedure of operation and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit with endotracheal tube inserted. After confirming her awareness and the absence of any neurologic disorder, extubation was performed in intensive care unit. To minimize the risk of hemorrhage of the anastomosis site, anticoagulation was performed with caution under the collaboration of general surgery and cardiology. It was started with low molecular weight heparin 3 days after the operation and oral warfarin was added 5 days after the operation. After 4 weeks, cardioversion was successfully performed to turn into normal sinus rhythm.

Discussion

Mesenteric infarction is induced by the embolism in the left atrium, left ventricle, and heart valves; the superior mesenteric artery is anatomically the most vulnerable to infarction due to its large diameter and the acute angle takeoff from the aorta, but the inferior mesenteric artery is rarely vulnerable due to its small diameter [1,2]. For preventing injury from ischemia, the main mesenteric blood vessels have extensive collateral circulation; however, when the mesenteric arterial embolism occurs, the mid-segment of the jejunum, which is the farthest from the collateral circulation of the celiac artery and inferior mesenteric artery, becomes most vulnerable to ischemia [1]. An acute hypoperfusion state induced by mesenteric arterial vascular disorder forms 60-70% of the total mesenteric ischemia with mortality rate exceeding 60% [3].

Symptoms can vary from acute severe, nonremitting abdominal pain to vague abdominal pain. And associated symptoms may include nausea and vomiting, transient diarrhea, and bloody stools. However the absence of any specific clinical symptom and no indicator shown in blood test or plain X-ray make early diagnosis challenging which may end up in delayed treatment. It is highly suspicious in aged patients with AF and a previous history of cardiac and vascular disease like recent myocardial infarction, rheumatic heart disease, and recent cardiac catheterization. Mesenteric angiography is the most reliable diagnostic tool and also helps locating exact site of blockage [4]. An early angiography on a patient suspected of arterial ischemia is widely accepted to decrease the mortality rate of mesenteric ischemia patients.

There was no comment about the thrombus in the LA and the LAA on the pre-operative TTE examination; it is difficult to observe a LAA by TTE, so the sensitivity of the TTE of the LA or LAA is known as 39-63% [5,6]. In contrast, by TEE, observing the posterior structures of the heart, such as the LA and LAA is much easier, the sensitivity and the specificity of thrombus in the LA was reported as 93-100% and 99-100%, respectively [5,6]. TEE of patients with AF shows a SEC in the LA or LAA, which is known to increase the risk of thromboembolism [7]. Estimation of blood flow velocity in the left or right atrium and left and right atrial appendage permits a more quantifiable measure of stasis [8]. The risk of stroke increases sharply with marked reductions in blood flow velocity (<15 cm/sec), particularly in the LAA or posterior left atrium [9].

SEC refers to the presence of dynamic, smoke-like echoes seen during echocardiogram in the LA or LAA; it is known that SEC is formed by a red blood cell rouleaux formation on stagnant flow condition [10]. Difficulty to quantificate SEC by identifyimg as a fluid whirlwind of smoke is due to differences between the frequency and the gain of an echocardiogram probe. SEC may be missed in the case where the gain is too low or the test room is too bright. SEC should be observed under high gain with a high-frequency probe over 5 MHz which a uniform noise is seen in the LA. The LAA peak outflow velocity can be estimated by TEE and SEC semiquantitatively graded as marked or dense if present throughout the entire cardiac cycle, or faint when intermittent [11].

The goal of treating AF include maintaining sinus rhythm, controlling heart rate, and preventing thromboembolism by using anticoagulant therapy; the risk stratification of thromboembolism is most important for anticoagulant therapy. The high risk factors of thromboembolism include a previous history of thromboembolism, mitral valve stenosis, and a mechanical valve; moderate risk factors are ages over 75, hypertension, heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 35%, and diabetes. Females, ages from 65 to 74, coronary arterial diseases, and thyrotoxicosis correspond to low risk factors. During anticoagulation therapy, aspirin 81-325 mg/day should be taken in the case where there are no risk factors or only low risk factors; aspirin or warfarin (INR 2-3) should be taken in case of 1 moderate risk factor. Warfarin should be taken in case of 2 or more moderate risk factors or the existence of a high risk factor in case of a mechanical valve, INR should be maintained more than 2.5 at minimum [12].

CHADS2 (Cardiac Failure, Hypertension, Age, Diabetes, Stroke [Doubled]), another stroke risk stratification, scores 1 for heart failure, hypertension, ages over 75, and diabetes and scores 2 for a previous history of a stroke or transient ischemic attack and adds the scores, and then classifies score 0 as a low risk group, scores 1 as a moderate risk group and scores over 2 as a high risk group. Aspirin is used for the low risk group, aspirin or warfarin is selectively used for the moderate risk group, and the high risk group with scores over 2 should be performed with anticoagulant therapy [12,13]. In this case, the patient should have been initiated an anticoagulant therapy considering her high blood pressure, congestive heart failure, and chronic cerebral infarction detected by the brain CT. In addition, aged patients with AF showing mitral annular calcification on echocardiography, there is a high potency of thromboembolism, even without mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation, or prolapsed leaflet [14].

The authors suggest that risk stratification before operation should be performed on AF patients with thromboebolism risk factors; hemodynamic and neurologic observation are needed on the induction, maintenance, and emergence period of anesthesia; TEE during operation can be helpful for these patients.