|

|

|

|

Abstract

The laryngeal mask airway (LMA) Classic™ and Air-Q® are supralaryngeal devices used for airway management in routine and difficult pediatric airways. We describe a novel two-stage technique of insertion of the LMA Classic™ awake prior to induction of anesthesia, to assure oxygenation and ventilation, and after induction removal and placement of the Air-Q® for intubation using the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope. The LMA Classic's™ pliable design and relatively small size allow it to be easily placed in awake infants. In contrast, the Air-Q® is an excellent device for intubation because of its larger internal diameter and removable 9 mm adapter. Our goal was to reduce unpredictability and potentially increase the safety of induction of anesthesia and intubation in infants with Pierre Robin sequence. By using these devices in a two-stage approach we created a technique for consistent oxygenation, ventilation, and intubation in these infants.

Neonates with Pierre Robin sequence may develop complete airway obstruction even while awake [1]. Inhalational inductions in these infants may be very unpredictable ranging from difficult bag mask ventilation leading to desaturation and/or requiring the lateral or prone position. Intubation is often difficult as it is frequently difficult or impossible to visualize the glottic opening with direct laryngoscopy. For experienced laryngoscopists, the availability of newer video laryngoscopic techniques or the use of a flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope (FFB) [2] may facilitate airway management in these patients.

The laryngeal mask airway (LMA) Classic™ and Air-Q® are supralaryngeal devices used for airway management in routine and difficult pediatric airways [2,3,4] (Fig. 1). We describe a novel two-stage technique in which the LMA Classic™ is inserted awake prior to induction of anesthesia to assure oxygenation and ventilation. After induction the LMA Classic™ is removed and the Air-Q® is placed to facilitate intubation using a pediatric FFB. The LMA Classic's™ pliable design and relatively small size allow it to be more easily placed in awake infants [3]. In contrast, the Air-Q®, because of its larger internal diameter and removable 9 mm adapter, is an excellent device for intubation [4].

We describe our successful airway management of two neonates with Pierre Robin sequence using this two-stage technique.

A 13-day-old, 3.4 kg male infant with Pierre Robin Sequence born at 39 weeks by Cesarean-section was scheduled for mandibular distractor placement due to ongoing respiratory distress with intermittent airway obstruction. The infant had to be maintained in the prone position with nasal cannula oxygen to avoid respiratory decompensation. The patient was transported to the operating room (OR) in the prone position with supplemental oxygen and a 24 G IV in place. In the OR prior to induction the infant was premedicated with 80 µg of atropine IV. The patient was placed in the lateral position and an LMA Classic™ #1 was easily inserted into the patient awake. This was well tolerated by the infant. The LMA Classic™ was then connected via a standard pediatric circle system to the anesthesia machine. The patient continued to ventilate spontaneously with an appropriate end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) tracing and no physical signs of upper airway obstruction. The patient was then moved to the supine position. The fresh gas flow was set at 6 L/min of oxygen. After 1 minute of preoxygenation via the LMA Classic™, the sevoflurane vaporizer was turned to 8%. The infant continued to breathe spontaneously and after approximately 1 minute his heart rate began to decrease and spontaneous movements of his extremities ceased. At this point the patient's ventilation was assisted. Once the ability to ventilate via the LMA Classic™ was assured, rocuronium 3 mg IV was administered to facilitate placement of the Air-Q® and intubation. The sevoflurane concentration was reduced to 1.2%. The LMA Classic™ was removed and was immediately replaced with an Air-Q® 1.0. No attempt was made to mask ventilate the patient. The patient was ventilated via the Air-Q®, and adequate chest excursion and good ETCO2 were noted. A 2.8-mm inner diameter Karl-Storz FFB was loaded with a 3.5 uncuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) [5]. The ETT was easily placed in the trachea via the Air-Q®. The FFB was removed and the ETT adapter was replaced to confirm endotracheal placement of the ETT. Good chest excursion and ETCO2 were observed. The Air-Q® "Pusher" was used to hold the ETT in place as the Air-Q® was removed. The adapter was replaced and ETT was secured at 10.5 cm at the alveolar ridge. Once secured, the surgery proceeded as planned. At no time during induction or intubation was the patient difficult to ventilate, and the patient remained well saturated throughout.

The patient remained intubated following the procedure and was extubated without event 6 days later.

A 4.4 kg male born via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery at 39 weeks, was noted to have a hypoplastic mandible and high arched palate, and posteriorly displaced tongue consistent with Pierre Robin Sequence. On admission to the neonatal intensive care unit the patient was noted to have ongoing intermittent airway obstruction and respiratory distress with attendant hypercapnia. The patient was given supplemental oxygen and maintained in the prone position.

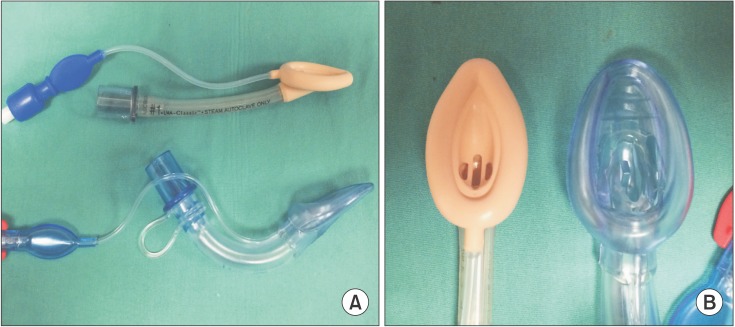

The patient was brought to the OR on day-of-life 21 with a 22 G IV in place. The patient was positioned supine and an LMA Classic™ #1 was easily inserted with the patient awake. The patient continued to breathe spontaneously for approximately 1 minute with breath sounds and a normal appearing ETCO2 tracing. We performed an inhalational induction via the LMA. As the patient was induced we transitioned from spontaneous ventilation to hand-assisted ventilation. Rocuronium 5 mg was administered, and the sevoflurane was reduced to 2% while the patient was hand ventilated. The LMA was then removed and a 1.0 Air-Q® was placed. We continued to ventilate easily and then intubated the patient through the 1.0 Air-Q® with a 3.0 uncuffed ETT over a 2.8 mm Karl-Storz FFB as described above. After confirming tracheal placement by auscultation and ETCO2, the leak was found to be excessive at 15 cmH2O. The ETT tube was removed and the Air-Q® was replaced. We then intubated the patient again using a FFB through the Air-Q® with a 3.5 uncuffed ETT. The ETT was secured and repeat bronchoscopy and chest X-ray were performed to verify the tube placement above the carina. These steps are illustrated photographically in Fig. 2. At no point during the induction and intubation was ventilation difficult, and the patient remained well saturated throughout. The patient remained intubated after the procedure and was extubated without event on postoperative day 5.

Induction of general anesthesia and bag mask ventilation in neonates with Pierre Robin Sequence and other syndromes associated with a difficult airway may be challenging [2,6,7].

Additionally, because of the cephalad position of the glottis, the visualization of the larynx using conventional laryngoscopy or video laryngoscopy may be impossible, necessitating the use of a FFB [2]. The literature describes the use of various supralaryngeal devices as conduits for intubation and ventilation in children and infants with a difficult airway [2,8,9,10,11,12]. The uniqueness of our technique is that we used a two-stage approach having placed the LMA Classic™ in these infants awake first. This alleviated much of the upper airway obstruction that was present. If the LMA Classic™ had not seated well, or the patient could not be ventilated, then we would have simply removed it and attempted to place it again with the patient awake and breathing spontaneously. In both of these infants we had not begun to induce anesthesia, so there was a much higher margin of safety. Also in the event that we had been unable to place the LMA Classic™ it could've been removed to attempt an awake laryngoscopy or awake fiberoptic intubation, or proceed with a mask induction.

In both of these infants the LMA Classic™ seated well after a single attempt. As these infants undergo inhalational induction of anesthesia even in the lateral or prone position airway obstruction may sometimes worsen. With the LMA Classic™ in place over the glottis we overcame this potential issue. This allowed for a more favorable starting point from which to induce general anesthesia and a more straightforward and predictable approach to maintaining adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

Once the patients were induced and ventilating via the LMA Classic™ we paralyzed the patient with a nondepolarizing muscle relaxant to eliminate laryngeal reflexes, patient movement, and facilitate placement of the larger and more rigid Air-Q®. Because we had a well-seated LMA Classic™ in place we felt that this was extremely predictive of repeat placement of the LMA Classic™ in the event we were unable to place the Air-Q®. Also we felt placement of the PLMA was predictive of successful placement of the Air-Q® 1.0. We are not aware of any published data to support the hypothesis that previous successful placement of an LMA Classic™ is very predictive of being able to replace it were it removed. However, it has been our clinical experience that initial success in placement of a supralaryngeal devices, even in small children and infants, is highly predictive of future successful placement and good seating. We have attempted to place the Air-Q® in the past in several other awake infants. Although we were successful in one, it was clear that its size and relative rigidity make it relatively more challenging to place in the awake infant. This made it a less ideal choice, and potentially a liability, as the additional force needed for placement may have potentially led to mucosal abrasion and pharyngeal injury in these infants. We then intubated via the Air-Q® as has been previously described.

The literature is very clear that the "can't intubate, can't ventilate" scenario in pediatric patients tends to be associated with very poor outcomes [13]. With this very real concern in mind many practitioners may attempt to perform awake laryngoscopies or awake fiberoptic intubations in these patients [2,6]. This can be extremely challenging and frequently may be unsuccessful. It may also represent a situation of increased stress on the infant. Cain et al. [3] reported attempting to perform an awake laryngoscopy as well as an awake fiberoptic intubation in an infant with Pierre Robin Sequence that was deemed too high-risk for a mask induction. This conservative approach may be deemed the safest but frequently has also been unsuccessful. After failing with these more conventional awake approaches, the authors reported placing a disposable LMA awake and inducing general anesthesia with this device in place [2]. Following induction they report being unable to intubate via the disposable LMA and switched it to an LMA Classic™ through which they were able to intubate. Although used successfully for intubation in this and several other reports, it has been our experience and that of others such as, Darlong et al., that the Air-Q® is better designed for intubation when compared to the LMA Classic™ [3]. Asai et al. [6] report placement of the LMA Classic™ awake in several infants including two with Pierre Robin Sequence after several failed attempts at awake fiberoptic intubation secondary to hypoxia. They were then able to successfully intubate these children awake using a FFB via the LMA Classic™. Their findings of consistent oxygenation and ventilation in these infants are important and represent a conceptual starting point for our two-stage technique.

We differed from this approach at two points in that we used the LMA Classic™ not only to ventilate and oxygenate but also to induce anesthesia. Secondly, we administered relaxant to these infants with the LMA Classic™ in place to prevent patient movement and laryngeal reflexes that might impede intubation. The presence or absence of relaxant does not alter the rate of future success or failure of placement of a supralaryngeal device. In this situation intact airway reflexes and the presence of spontaneous ventilation can lead to coughing, laryngospasm, breath holding during attempts to intubate. This represents a far greater likelihood of desaturation and the potential to have to emergently administer succinylcholine to relax the glottis.

In conclusion, we believe this two-stage approach using the LMA Classic™ and Air-Q® represents a more consistent and general approach to maintaining adequate oxygenation and ventilation prior to and after induction of anesthesia and later for intubation in high-risk neonates with Pierre Robin sequence.

References

1. Darlong V, Biyani G, Pandey R, Baidya DK, Punj Ca. Comparison of performance and efficacy of air-Q intubating laryngeal airway and flexible laryngeal mask airway in anesthetized and paralyzed infants and children. Paediatr Anaesth 2014; 24: 1066-1071. PMID: 24961960.

2. Fiadjoe JE, Stricker PA, Kovatsis P, Isserman RS, Harris B, McCloskey JJ. Initial experience with the air-Q as a conduit for fiberoptic tracheal intubation in infants. Paediatr Anaesth 2010; 20: 205-206. PMID: 20078822.

3. Cain JM, Mason LJ, Martin RD. Airway management in two of newborns with Pierre Robin Sequence: the use of disposable vs multiple use LMA for fiberoptic intubation. Paediatr Anaesth 2006; 16: 1274-1276. PMID: 17121559.

4. Jagannathan N, Kho MF, Kozlowski RJ, Sohn LE, Siddiqui A, Wong DT. Retrospective audit of the air-Q intubating laryngeal airway as a conduit for tracheal intubation in pediatric patients with a difficult airway. Paediatr Anaesth 2011; 21: 422-427. PMID: 21175955.

5. Fiadjoe JE, Stricker PA. The air-Q intubating laryngeal airway in neonates with difficult airways. Paediatr Anaesth 2011; 21: 702-703. PMID: 21518107.

6. Asai T, Nagata A, Shingu K. Awake tracheal intubation through the laryngeal mask in neonates with upper airway obstruction. Paediatr Anaesth 2008; 18: 77-80. PMID: 18095971.

7. Barch B, Rastatter J, Jagannathan N. Difficult pediatric airway management using the intubating laryngeal airway. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012; 76: 1579-1582. PMID: 22889575.

8. Jagannathan N, Sequera-Ramos L, Sohn L, Wallis B, Shertzer A, Schaldenbrand K. Elective use of supraglottic airway devices for primary airway management in children with difficult airways. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 742-748. PMID: 24322570.

9. Kim YL, Seo DM, Shim KS, Kim EJ, Lee JH, Lee SG, et al. Successful tracheal intubation using fiberoptic bronchoscope via an I-gel™ supraglottic airway in a pediatric patient with Goldenhar syndrome -A case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol 2013; 65: 61-65. PMID: 23904941.

10. Ferrari F, Laviani R. The air-Q(®) intubating laryngeal airway for endotracheal intubation in children with difficult airway: our experience. Paediatr Anaesth 2012; 22: 500PMID: 22486912.

11. Sinha R, Chandralekha , Ray BR. Evaluation of air-Q™ intubating laryngeal airway as a conduit for tracheal intubation in infants--a pilot study. Paediatr Anaesth 2012; 22: 156-160. PMID: 21973052.

12. Sunder RA, Haile DT, Farrell PT, Sharma A. Pediatric airway management: current practices and future directions. Paediatr Anaesth 2012; 22: 1008-1015. PMID: 22967160.

13. Cladis F, Kumar A, Grunwaldt L, Otteson T, Ford M, Losee JE. Pierre Robin Sequence: a perioperative review. Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 400-412. PMID: 25046788.

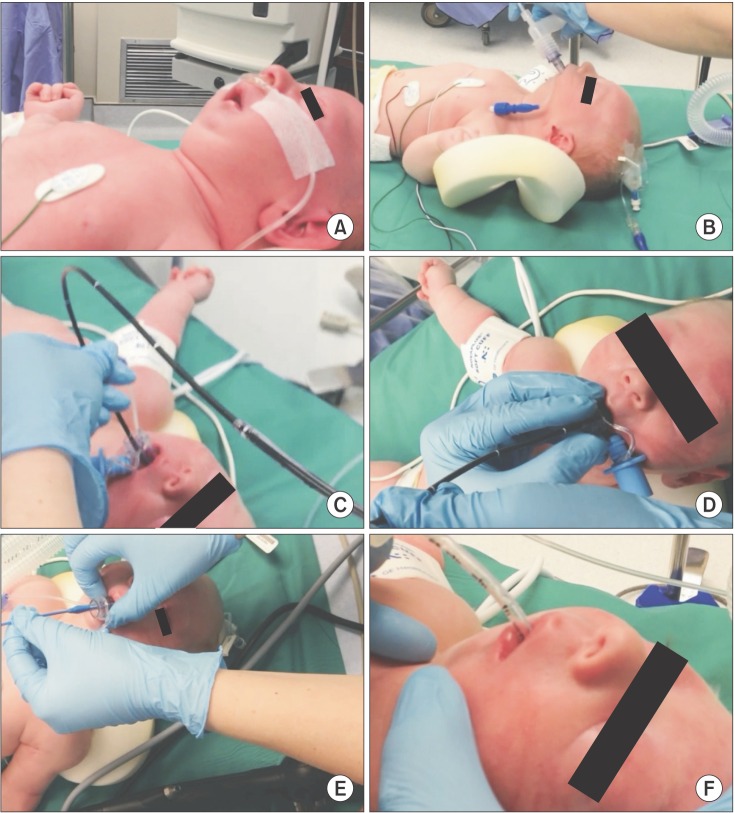

Fig. 1

(A) Laryngeal mask airway (LMA) ClassicTM #1 and Air-Q® 1.0; (B) Larger airway bowl of Air-Q® 1.0 compared to that of the LMA Classic™ #1.

Fig. 2

(A) Pierre Robin Sequence infant prior to induction; (B) Laryngeal mask airway (LMA) Classic™ inserted awake; (C) Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope (FFB) placed through Air-Q® 1.0; (D) Endotracheal tube (ETT) placed over FFB with patient induced and relaxed; (E) Air-Q® Pusher used to remove Air-Q®; (F) ETT in place.